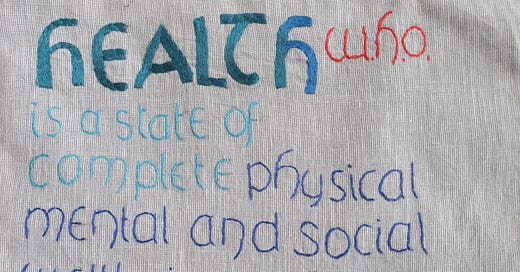

WHO definition of Health: ‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity… The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.’

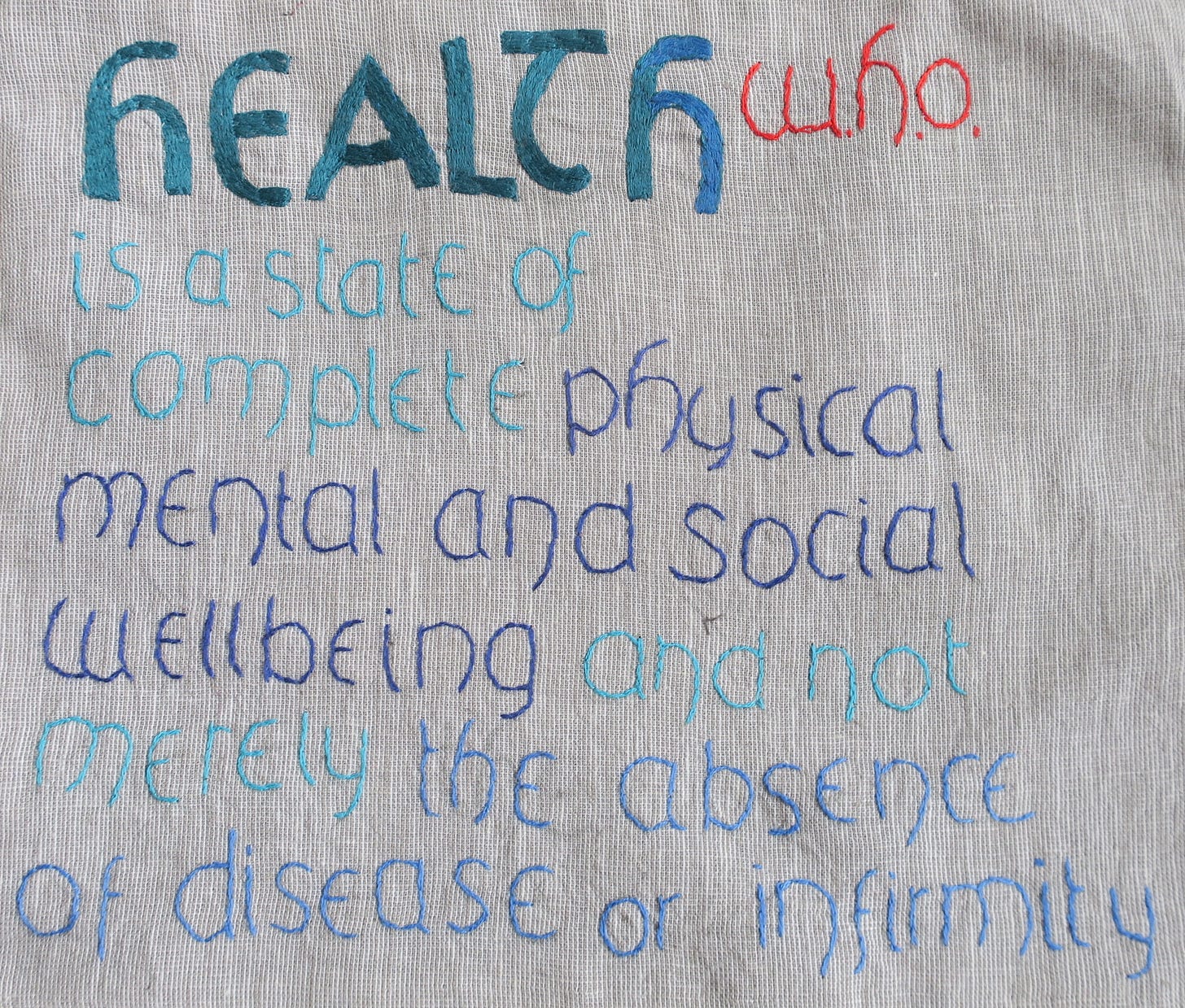

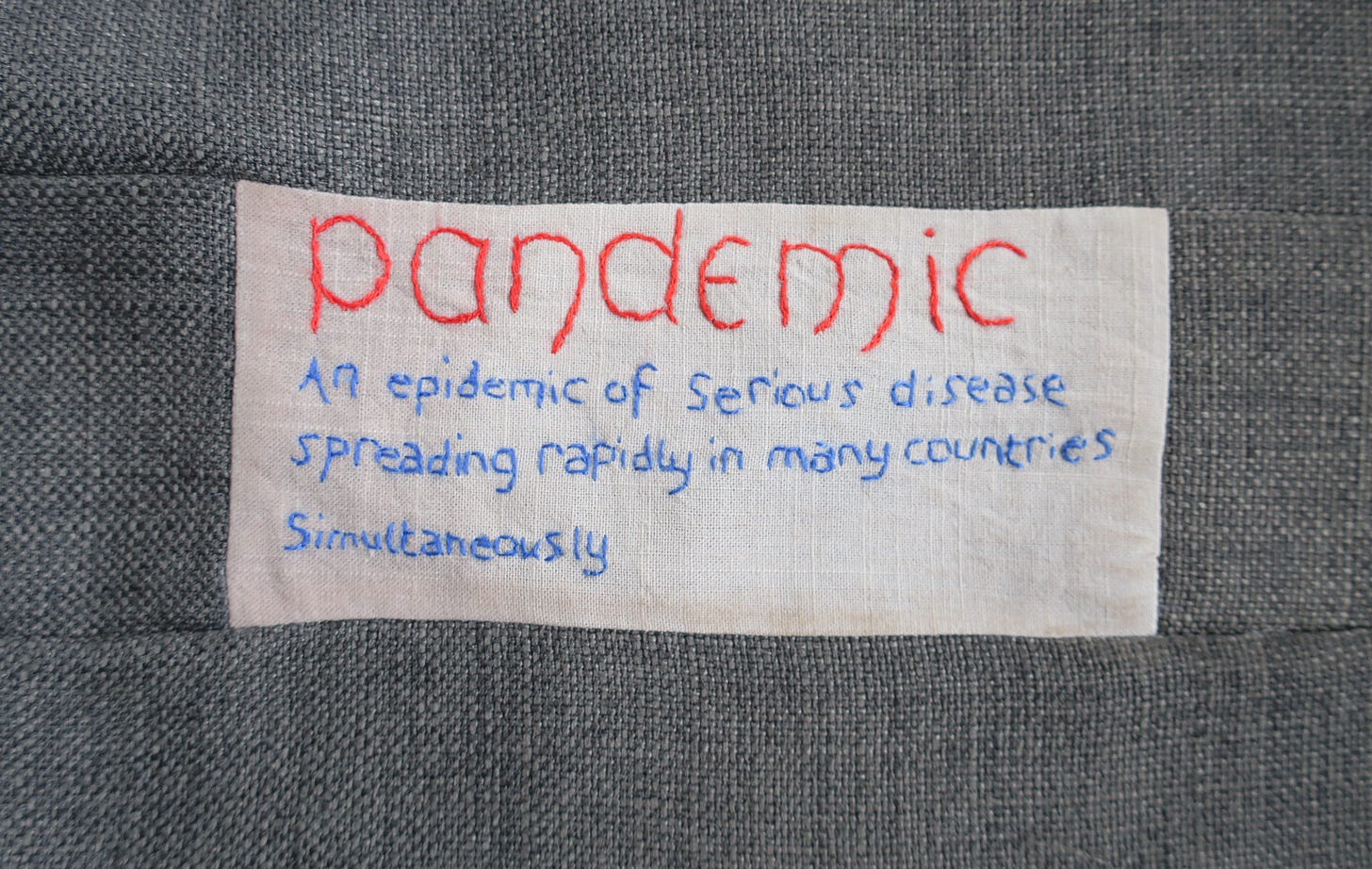

In Spring 2020 the virus called SARS-COV2 emerged from nowhere to infect our collective global consciousness and turn our world upside down. International Public Health strategy switched focus overnight and for three long years it was all about the virus.

The new definition of ‘Health’ appeared to be ‘the absence of the disease, Covid-19’, or of Covid-related infirmity, Long-Covid in all its guises. The old positive standards of ‘complete physical, mental and social well-being’ were now to be considered a selfish indulgence, something impossible to aim for and henceforth these lofty goals should be deferred until ‘after Covid’.

To talk of ‘fundamental rights to health’ became taboo, and frankly a bit libertarian. In our battle to vanquish the virus, it would become necessary to lower our standards of health, until some nebulous point in the future when we would all be safe.

Swine Flu - The Dry Run

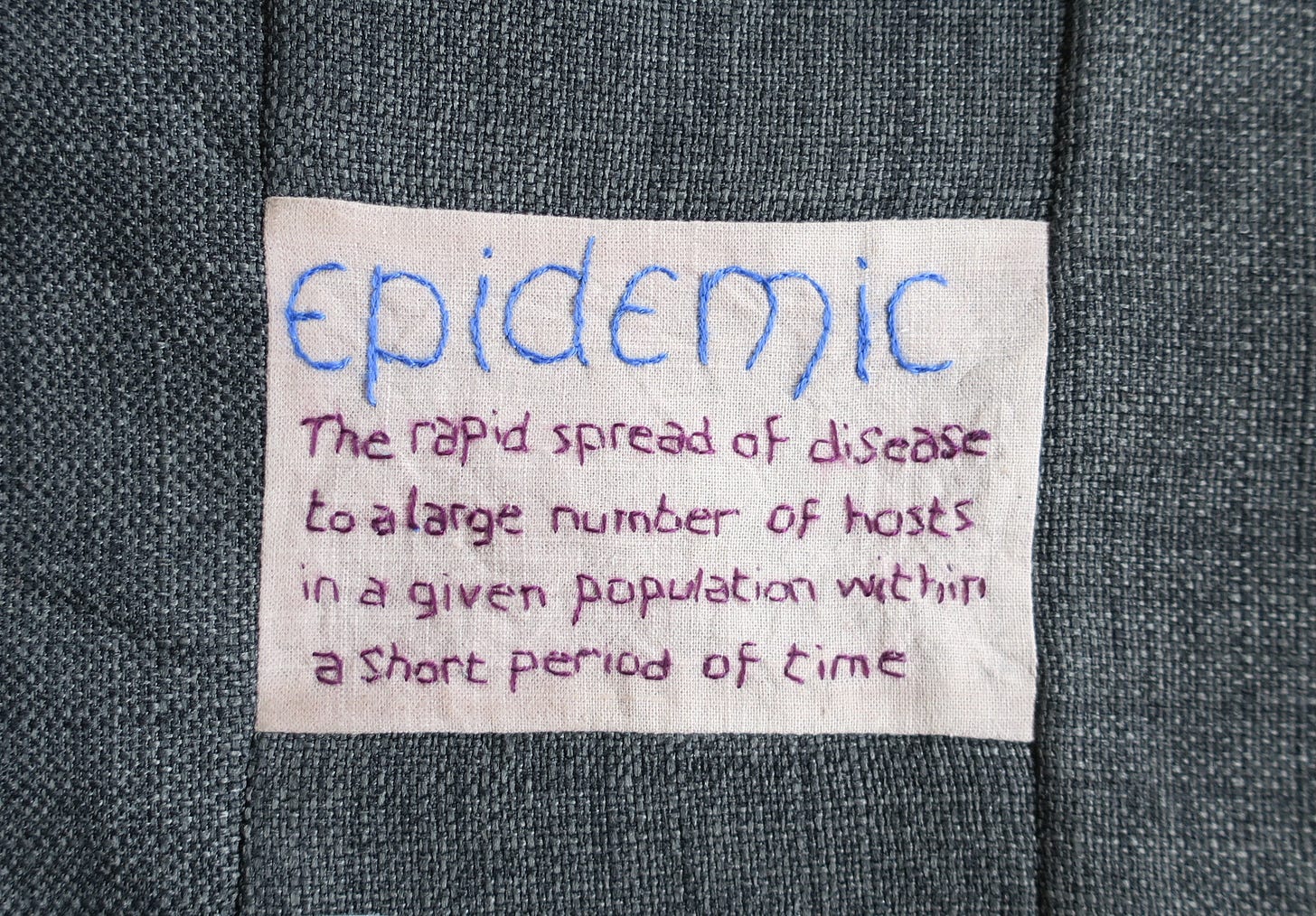

When news emerged in 2020 about a novel deadly virus from China, I was initially sceptical. Some of the early media Covid theatre felt familiar. I’ve no doubt my own caution about Covid was borne of past experience with the H1N1 2009 Swine flu panic.

In the wake of the Summer of Swine Flu madness, and after the UK government had forked out nearly £500 million on antivirals, there was a sense of bemusement at what had just happened. The modellers had been mistaken, a cautionary tale. The World Health Organisation (WHO) had faced criticism for exaggerating the danger of Swine Flu and spreading fear and confusion.

For an unsettling few weeks, the NHS had been thrown into chaos. We’d flirted with Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and practiced decontamination rituals. In the pandemonium, cases of sepsis and other serious illness were misdiagnosed as flu, leading to near misses and no doubt to avoidable deaths.

In England, as part of the 2009 Emergency Pandemic Response, lay people and nurses on dedicated hotlines were trained at warp speed to triage, diagnose and treat Swine Flu. With an obvious bias to diagnosis, they seemed to diagnose it rather a lot. The antivirals didn’t work and weren’t needed; these drugs made children vomit, leading to anxious follow-up calls from parents, worried about the side effects of treatment and worried about the consequences of stopping the antivirals.

It would later take 4 years of exhaustive work by the Cochrane review group and investigative journalists to get the data behind the Tamiflu trials, which eventually showed that these antiviral drugs did not work and risks outweighed benefits for most people.

Swine Flu hotline operators called ambulances for people who in fact didn’t need them, because their algorithms told them to, and because they were terrified of getting it wrong. I recall one exasperated patient reporting they’d cancelled the ambulance that they hadn’t asked for and didn’t need; they’d only wanted antibiotics for tonsillitis. Overnight, everything infectious had become ‘suspected Swine Flu’, as the diagnostic criteria broadened day by day. Sore throat, cough, earache, COPD, sinusitis - all Swine Flu - but at the end of that summer, I’m not sure I had seen a single convincing case of influenza.

Back in the day we didn’t have PCR tests. Who knows but maybe that was one reason why it was only a crazy Summer of Swine Flu Madness. The panic subsided and people moved on.