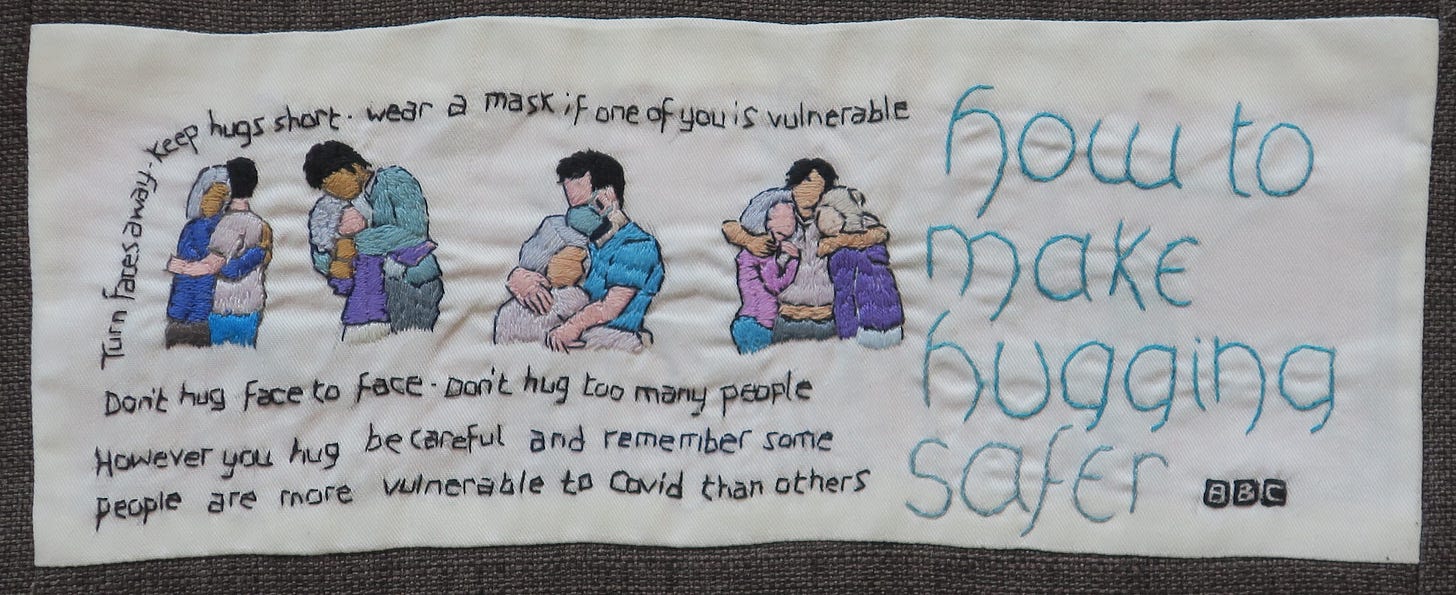

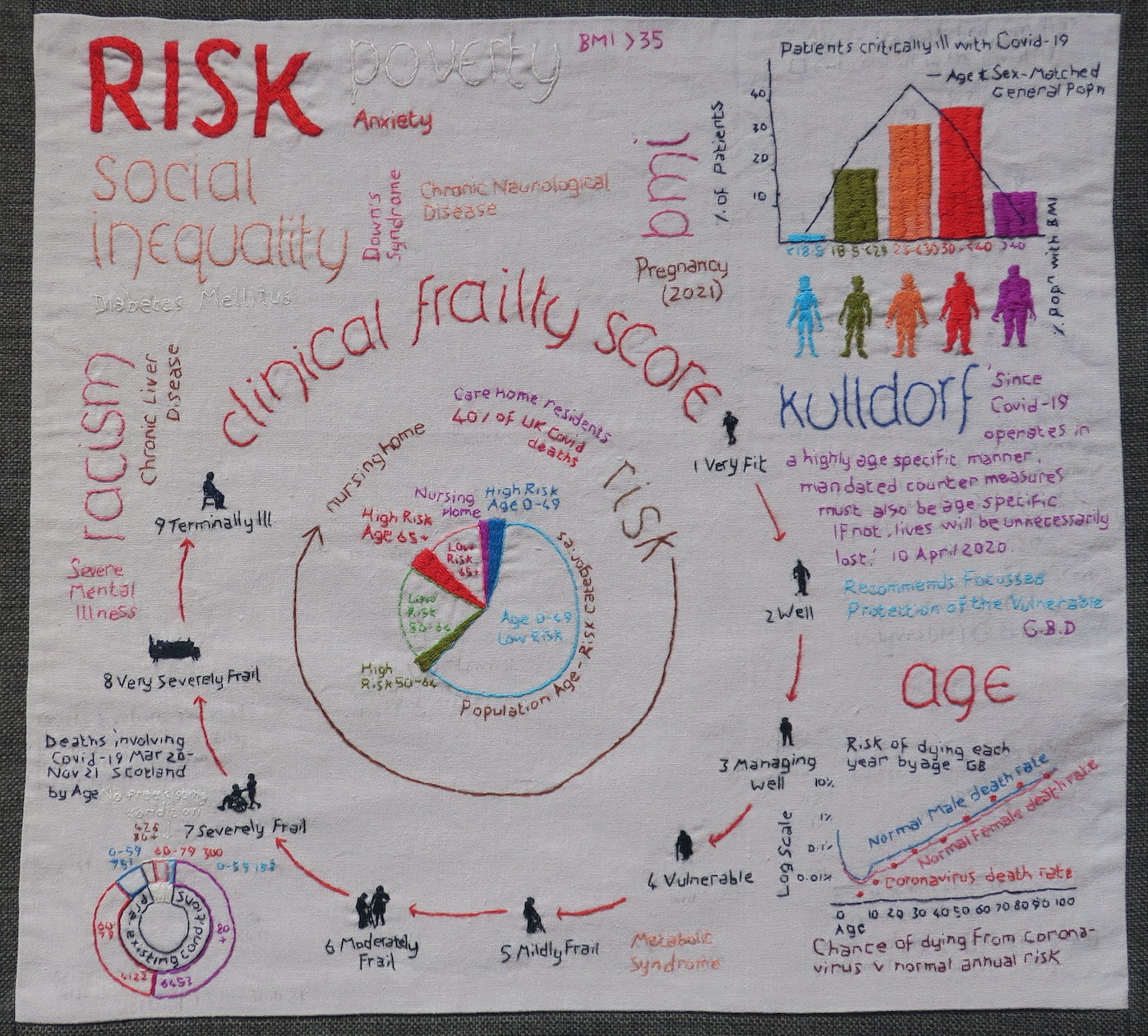

In 2022, a study in the Lancet reported Infection Fatality Rate (IFR) estimates for the period before the vaccine introduction and the widespread evolution of variants. We can see the extraordinary age gradient of Covid mortality:

After the age of 65, the CFR and IFR of Covid-19 rise steeply. In April 2021, Harman et al reported age- and gender-stratified CFRs for lab-confirmed Covid-19 in England during the second wave. The overall CFR was 1.4% and rates were higher in men than women. The highest CFR was in the over 80s (24.8%) followed by 70–79 year olds (12.8%), 60–69 year olds (2.4%). CFR in the under 50s was 0.05%

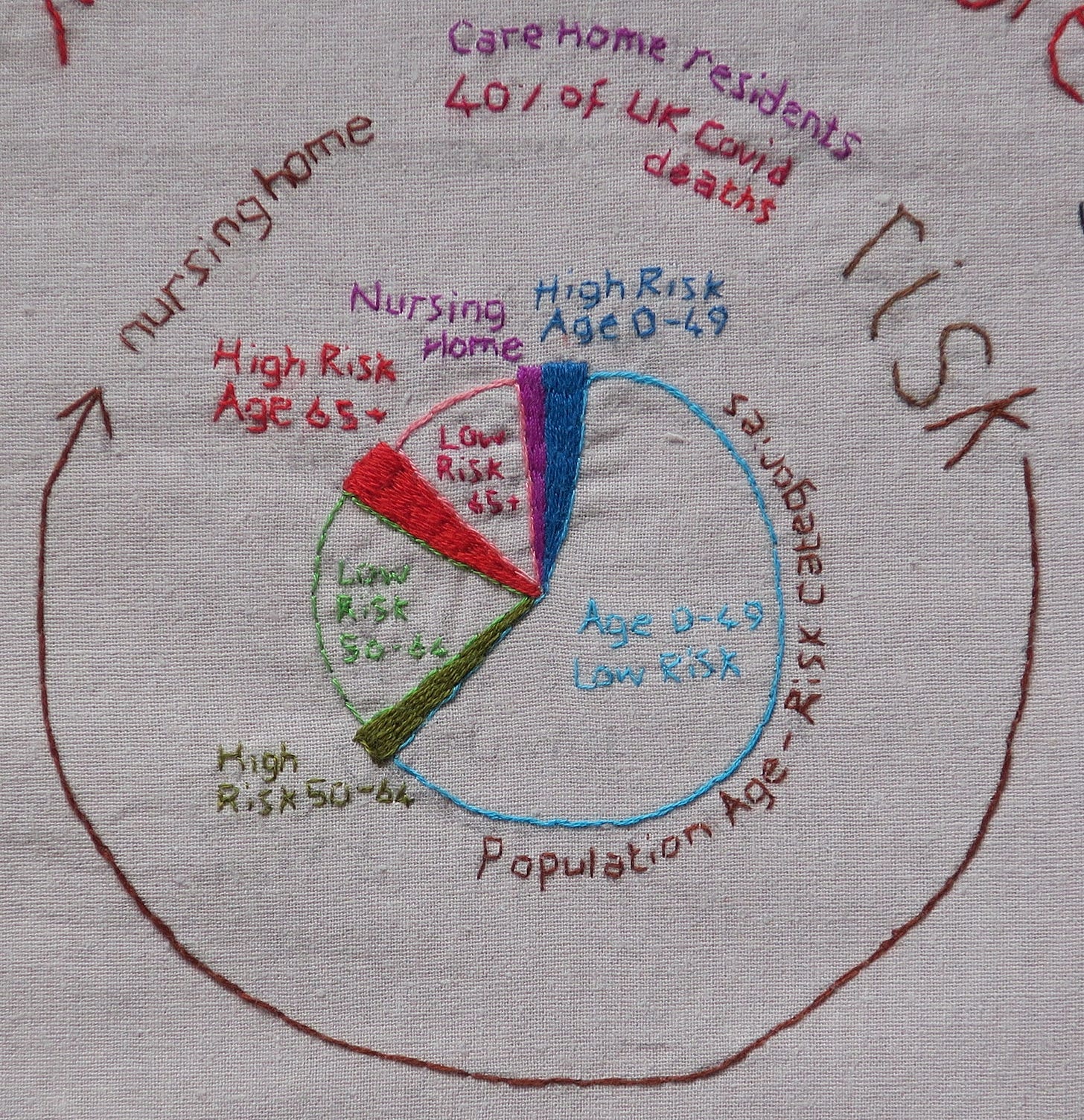

Paradoxically they found care home residents had a lower CFR (11.6%) than non-residents (22.9%), an artefact created by the policy of monthly testing of care home residents, detecting more mild and moderate cases. Care home residents diagnosed through routine screening had a much lower CFR (8.8%) than those diagnosed during outbreaks or hospital admissions (33.1%). This illustrates the influence of testing policy on Case Fatality Rates, but also draws attention to the issue of false positives and the ambiguity between CFR and IFR, when a case is defined by a positive lab test.

O’Driscoll et al calculated IFRs using seroprevalence studies in 45 countries and also showed that after the age of 65, IFR sharply rises. 65-69 year olds had an overall IFR just over 1%, the 75-79 age group had more than a 3% chance of dying if infected with SARS-Cov2, while people aged 80 and over had more than an 8% chance of dying. In all ages over 20, men were about twice as likely to die as women from COVID.

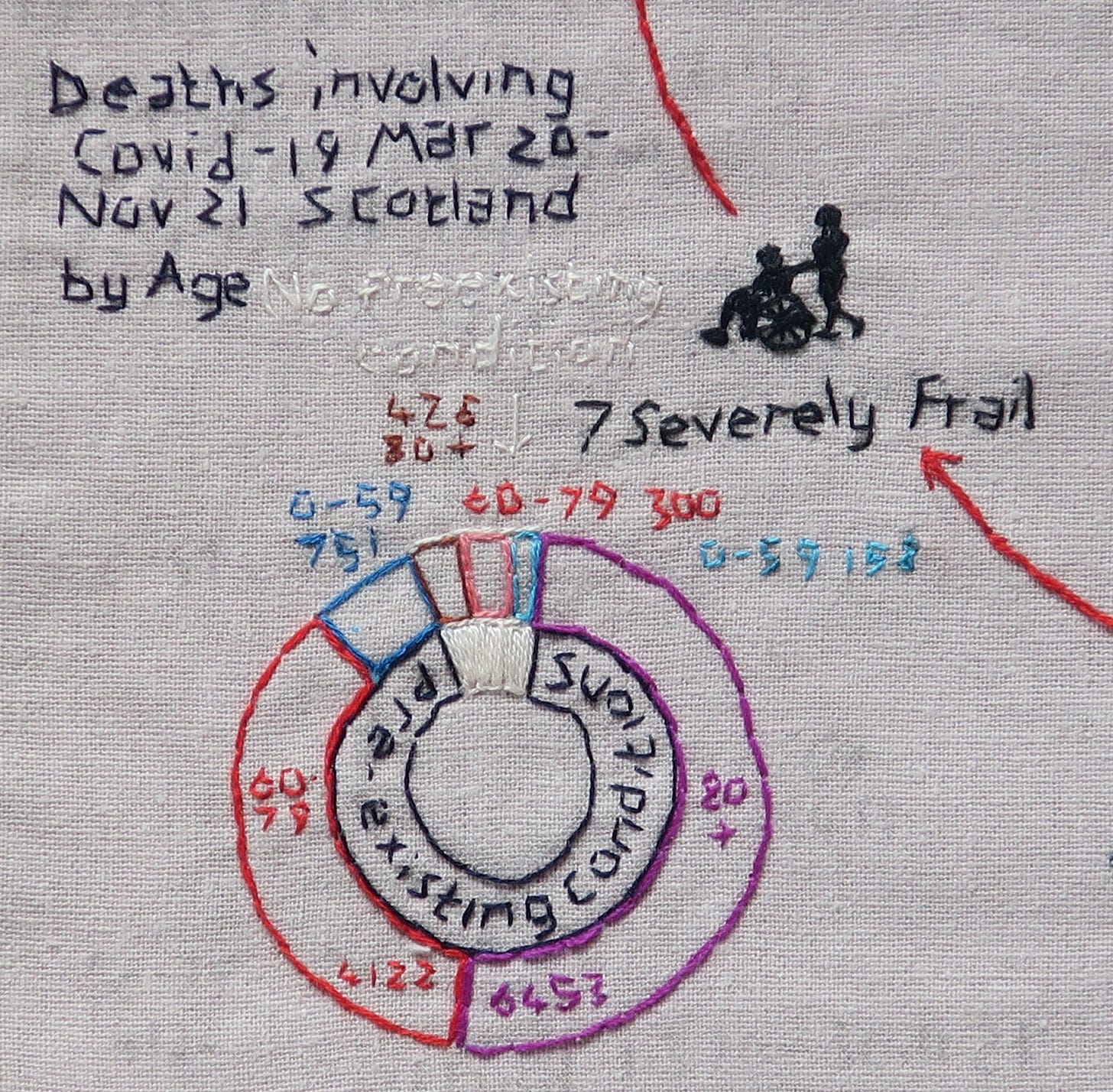

Between 2020 and 2022, 39% of all deaths involving Covid-19 in Scotland occurred in the over 85s, 70% were over 75 years old and 88% over 65. 1% (211) people were under 45 years old:

Covid-19 in the Care Home

Despite forewarning of the pandemic, as in other parts of the UK, lockdowns failed to prevent a devastating nursing home Covid-19 outbreak in my local community. Though 1 in 6 residents resisted infection, 1 in 3 died of Covid-19, the equivalent of about 6 months’s usual mortality in only a few weeks.

Nursing homes care for the frailest members of our community, a particularly vulnerable group of people. One 2013 study of care homes in England and Wales found that nursing home residents experience a 30.8% 1-year mortality compared with 22.3% in residential homes. Ordinarily, the average life expectancy in UK care homes is 24 months for care homes without nursing and 12 months for nursing homes. However the average life expectancy statistic is simplistic and can be an inaccurate prognostic indicator for an individual within a nursing home. Some residents die shortly after admission, while others live in care homes for much longer. It depends on their health, frailty and functional reserve.

The British Geriatrics Society define Frailty as ‘a distinctive health state related to the ageing process in which multiple body systems gradually lose their in-built reserves’. By their estimates, frailty affects 10% of over 65s and 25-50% of those aged over 85. In frailty, even seemingly minor stressors and infections can tip the balance, leading to serious adverse outcomes.

Frailty is not static (it can improve or deteriorate) and is not an inevitable consequence of ageing. But by the time an elderly person needs nursing care, they have generally declined to a very low level of function. Although they can survive for longer than expected at this very low level of functional reserve, they often won’t survive illnesses like ‘flu. If a person with poor reserve gets Covid-19, blood oxygen levels can drop quickly with minimal symptoms and even those with apparently ‘mild’ Covid illness can deteriorate rapidly. Even those who appear to have recovered from infection remain weakened by the virus, and they may die in the weeks or months after, of a seemingly unrelated cause.

In Scotland, 39% of all deaths involving Covid-19 occurred in care homes in 2020. Over the three years from 2020 to 2022 27% of all deaths involving Covid-19 occurred in care homes:

Staff in care homes are familiar with death. In bad ‘flu years they might have to cope with large numbers of deaths in the space of weeks. However Covid-19 was different. The fear of the virus, the early lack of PPE, the strain of so many deaths in a short period, the visiting restrictions, the scrutiny, the responsibility for keeping residents ‘safe’, the lack of support, the sense of injustice and moral distress and even, for some, concerns about the use of ‘end of life’ pathways. For care home staff, residents and family members, these have been traumatic years. Care workers were the unsung heroes of the pandemic but many have since left the profession.

Impact of Comorbidities

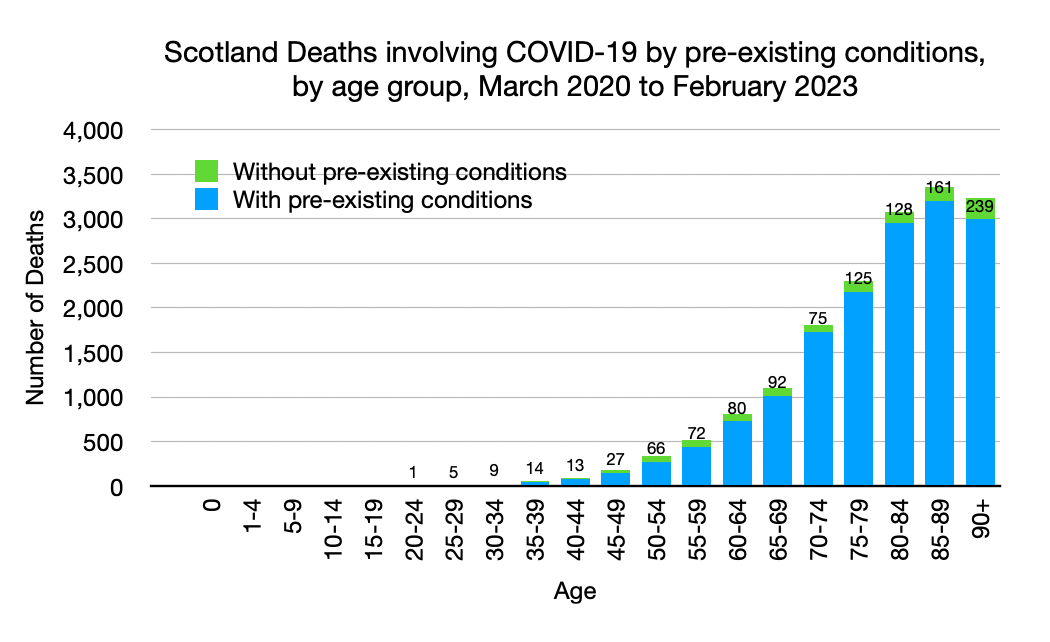

As people age, they usually acquire more co-morbidities. From March 2020 to February 2023 in Scotland, of 16933 deaths involving Covid-19, 1107 (6.5%) had no pre-existing health condition. In England and Wales 13% of Covid-19 deaths had no pre-existing health condition:

One in three UK adults with Covid-19 admitted to hospital as an emergency had five or more health conditions. 31% of recorded deaths due to Covid-19 in England and Wales in 2020-21 were in people with three or more pre-existing health conditions:

In England and Wales in 2020-2021, of the 1,194,256 deaths from all causes, 141089 (11.8%) were categorised as Covid-19 deaths.

In 2021, 31% of those who died of Covid-19 had heart disease/heart failure or cardiac arrhythmia (31% in 2020), 21% had Diabetes (20% in 2020), 19% Hypertension (18% in 2020), 17% had Dementia and Alzheimer’s (25% in 2020), 17% chronic lower respiratory disease (16% in 2020), 6% cerebrovascular disease (7% in 2020), 3% malignancy (2% in 2020) and 2.5% obesity (1.3% in 2020).

Of deaths in the 0-64 year group, 10.2% were obese (7.6% in 2020):

Like our patients, a significant number of healthcare workers or family members could be expected to have at least one co-morbidity. In Scotland in 2019, 66% of adults aged 16 and over were overweight including 29% who were obese. This contrasts with 33% having a weight in the healthy range. By 2021, 30% of adults were obese, including 4% morbidly obese.

Comparison to previous ‘flu epidemics

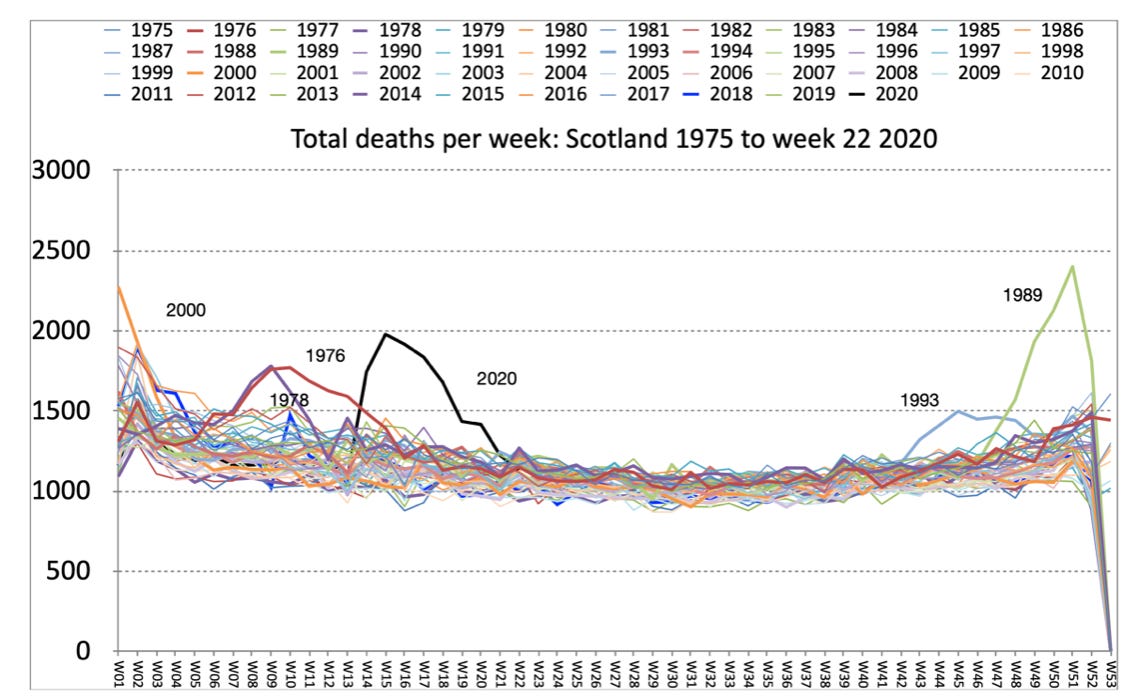

Winter 2017/2018 was the last severe flu outbreak in Scotland. I remember this well, as the 2017/18 ‘flu had caused a similar mortality impact on local care homes as Covid had in 2020. In 2020, some of the expected respiratory deaths were displaced by Covid-19 deaths, as illustrated in these graphs comparing 2018 and 2020 mortality for Scotland (not adjusted for an ageing population):

As is the case in flu epidemics, it is likely that some of these Covid-19 deaths were, in fact, deaths from secondary pneumonia. By applying machine learning to medical record data, scientists at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine found that secondary bacterial pneumonia was a key driver of death in patients with COVID-19. Interestingly, their study also negated the theory of the ‘cytokine storm’ being the driver of Covid-19 mortality.

In Scotland, more people died at the peak of the 1989 flu epidemic than the peak of the 2020 Covid-19 first wave. Most of us have no solid recollection of anything extraordinary happening in the winter of 1989, other than Band Aid reaching number 1 with ‘Do they know it’s Christmas?’ And yet something extraordinary did happen. There were 642 recorded ‘influenza’ deaths, compared to only 30 ‘flu deaths the following year. As we have seen, death certification is an inexact process and the crude total mortality spike suggests many more than 642 ‘flu deaths

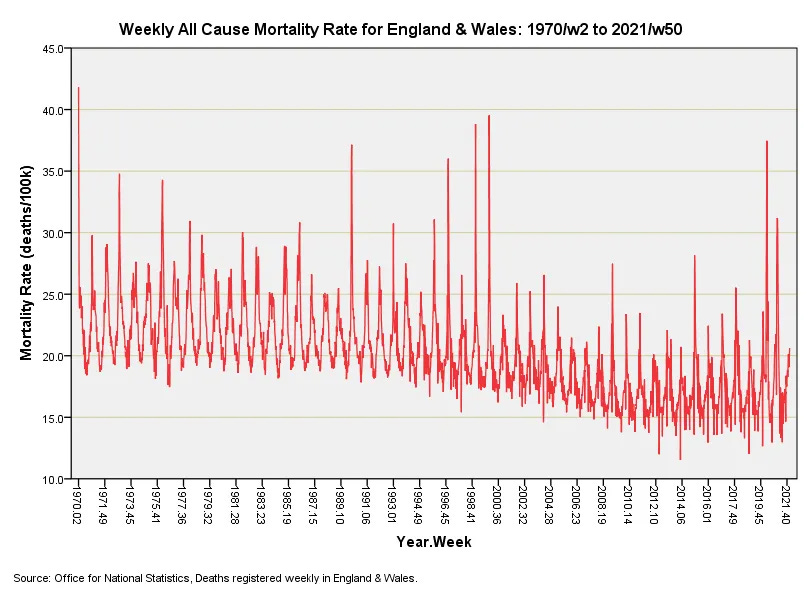

John Dee has plotted weekly crude mortality rates for England and Wales, dating back to 1970. In his graph, the mortality spike in 1989 is evident, though crude death rates in 1970, 1999 and 2000 surpassed even the 1989 and 2020 spikes:

Of course, we can never now know what crude mortality in Spring 2020 would have looked like without lockdowns, though Sweden, a country which famously didn’t lockdown, provides an important control that can increase our objective awareness.