Costs and Benefits of Risk Mitigation Strategies

On 13th March 2020 Sir Patrick Vallance advised BBC Radio 4 listeners,

”Our aim is to try and reduce the peak - not suppress it completely, also because most people get a mild illness, to build up some degree of herd immunity whilst protecting the most vulnerable”.

This comment evoked a backlash, with accusations of genocide from various quarters and we saw a pivotal shift in government attitude, policy and tone.

From that point on, there was unwavering focus on Covid-19 severe outcomes, but little mention any more of mild or moderate disease. As early as April 2020 we already had a wealth of data about the known risk factors for severe Covid-19 outcomes - the striking age and frailty gradient; the increased risk in men compared with women; the higher risk in Type 2 diabetes, obesity and metabolic syndrome; the higher risk for people from ethnic minority backgrounds; the low risk in children. But it wasn’t just the general population who now had a skewed risk perception, it was also healthcare staff, anchored by early mortality overestimates.

We shared a pervasive anxiety that any one of us may stand accused of spreading the virus through carelessness or breach in protocol. The low-intensity fear campaign increased our own paranoia when we saw how quickly it could become a witch-hunt, with a fearful public ready to angrily point fingers and assign blame in order to reduce their uncertainty. The natural response was to tighten up protocols, add more safety measures and reduce face to face interactions.

Already at this early stage, there was a spectrum of stringency measures across the NHS. How far teams took Covid mitigation might depend on their own local interpretation of national guidance (shaped by individual attitudes to risk). The early knowledge void for how to deal with a supposed deadly pandemic was just as often filled with bright ideas and strategies borrowed from social media and peer support groups. The principle underlying all this procedural change, was a belief that face to face human contact was now a potentially mortal danger and should, where possible, be the exception not the rule. Of course, you can’t run a health service without human contact and there would be unintended though not unpredictable, consequences.

One Essex GP was suspended for 6 months for failing to schedule face-to-face appointments for a patient who later ended up in hospital with a heart infection. At his tribunal, the doctor stated he chose not to conduct face-to-face consultations during Covid in 2020 and 2021 as he (the doctor) was obese and more vulnerable to the virus at the age of 66. Over a 9 month period, from May 2020, he allegedly remotely dealt with his patient through a series of telephone consultations. It is stated that he even arranged a CT scan without ever having examined the man, and prescribed more than one course of antibiotics as his patient clinically deteriorated and lost 3.5 stone.

By January 2021, the patient had become bed-bound due to lack of energy, but the doctor still appeared to view the world through the the narrowing lens of Covid (perhaps unsurprising given the media coverage at the time). In the medical notes, he summarised his telephone encounter with the patient, "Still feeling rubbish, beginning to go off food and drink, always feel cold now, has not done a Covid test, should try and book one as appears to have a viral infection”. Four days later the patient was hospitalised with endocarditis.

In his defence, the GP apparently said he was aware some GP surgeries did see patients in-person in 2020 and early 2021 but his did not, partly due to limited room availability, but also the need to keep patients isolated. He also stated the patient was "adamant that he did not want to go to hospital" as he was concerned about the care of his wife who was terrified of Covid.

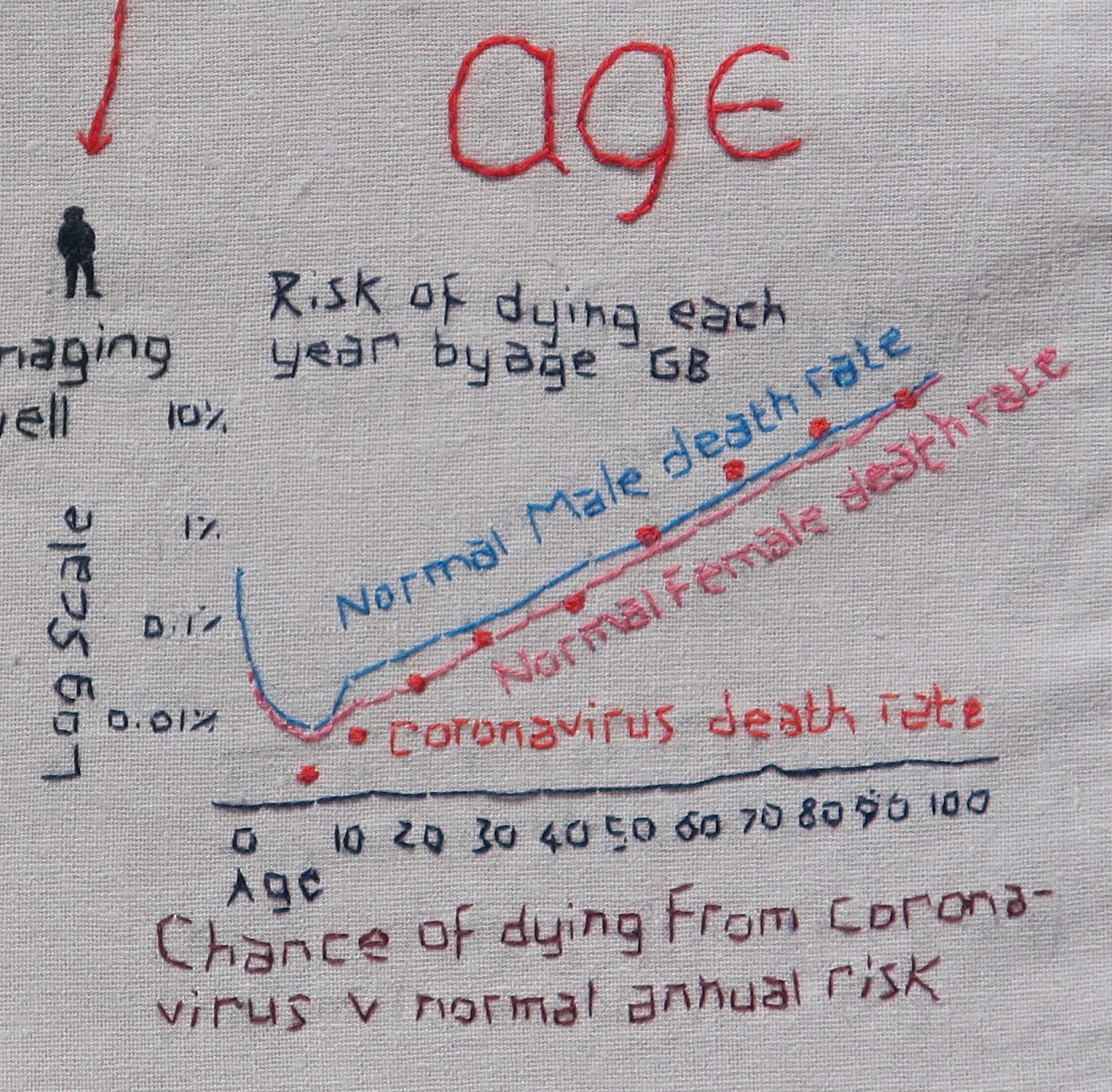

It is true that as an obese 66 year old man, the GP would have been more vulnerable to Covid-19, compared to his younger peers. A 66 year old man has a ‘normal’ annual risk of dying of 1 in 42, which can be expressed as a 2.3% annual risk of death. The March 2020 Imperial College risk tables predicted a Covid-19 IFR for a 60-69y old of 2.2% (hospitalisation rate 16.6%). So that fits with Spiegelhalter’s premise that his risk of death if infected with Covid-19 would be close to his normal annual risk of death.

By November 2021, a paper in Nature gave an IFR estimate of 1.452% for males aged 65 to 69. That means that for every 1000 men of that age infected with Covid-19, we might have expected 14 or 15 to die, and 985 or 986 to survive. Of these 15 men, about 2 would have no known co-morbidities, and 4 would have 1 co-morbidity, like obesity; though some of these men would be middle-class doctors, most would not.

A 2022 BMJ article lists the names of 52 UK doctors who had died of Covid-19 over 2 years, 49 of whom were included in the BMA memorial for doctors who died ‘fighting Covid’. Though the mean and median age of these doctors was 62y, the age range spanned from 44y (a GP trainee from Stevenage) to 84y (a GP from Clacton on Sea, remarkably still working at 84). The overwhelming majority of these doctors were of ethnic minority backgrounds; 18 were GPs.

These days it is unusual to hear of a working GP over 60y old. In 2021 there were only 1105 GPs in England over 65 as the average age doctors retire is now 59. So the 66 year old GP was an outlier, and as such, Covid-19 may have become a dread risk for him. Risk perception is a subjective experience, so it is not fair to criticise someone for developing a dread risk. Nevertheless, the consequences for his patient were disastrous.

Remote Consultations

It was disconcerting how quickly enthusiasts for change were asking, ‘how can we harness the power of the New Normal?’ Within weeks, some were predicting that we would never go back to the way we had worked before the pandemic. I found this a little depressing as I liked my job. Video and telephone consultations were seen as an opportunity for ‘freeing up time’, enabling clinicians to work from home, which would apparently solve the problems of staffing in the NHS. ln this utopian New Normal, people would learn to self-manage and take responsibility for their own health, allowing us to focus on those with the greatest needs. It was a boon time for companies offering technological solutions to the human access to care problem.

I was skeptical of the optimistic predictions of the telephone and IT evangelists. The ‘Telephone First’ system (whereby anyone wanting a GP appointment gets a call from the GP first), had already been widely trialled in England in the hope it would improve patient access and reduce GP workload. I had learnt through direct experience that it solved neither problem. Though the current driver for telephone triage was to reduce face to face contact and protect patients and staff from potential transmission of SARS-Cov2, the same issues would emerge. Initially the workload appeared to dramatically reduce but as people got used to the new system, the pressure ramped up and the system became more taxing and unmanageable. Some practices introduced an extra filter, asking patients to fill in an online form outlining their symptoms or enquiry; but could be another source of frustration for patients, leading to a perception that GPs were closed or were trying not to see them.

There are positives to full telephone access: for receptionists, it makes their job easier (but in doing so, deskills them); patients are generally able to access a GP for telephone advice quickly and there can be reduced waiting time to be seen, which can improve satisfaction. For some complaints, the query can be completed on the phone which saves time. There are, however, downsides. Though it leads to a significant reduction in face to face consulting time, there is empirical evidence that it doesn’t lead to cost savings, creates additional workload - especially for GPs - and generates demand where people would have self-cared. A 2004 Lancet study showed that 75% of those who received phone call from a GP needed another appointment within 28 days compared to 50% who saw a GP face to face. If a nurse triaged the call 88% needed another appointment within 28 days.

There are less quantifiable negative impacts: day after day of telephone consulting is stressful, can cause tension headaches, reduces job satisfaction and requires more clinician availability to take calls; it works better where the same person who triages the patient sees them face to face, but this requires a full cohort of GPs with sufficient numbers of face to face appointments or continuity of care becomes a problem; important diagnoses are missed; it can create a barrier to care.

Some people, put off by telephone triage, don’t make appointments. It disadvantages the old, the hearing impaired, the homeless, those with multiple co-morbidities, mental health issues, medically unexplained symptoms, children, and those with poor telephone or internet connections. Online consultations don’t work well in rural areas, where internet connectivity can be rudimentary. It discriminates against those without up to date computers or smart phones. People may feel unable to disclose their problems over the phone or in an online form. Most GPs have memorable past ‘by the way…’ serious diagnoses like cancer - where the patient gets to the crux of why they are presenting only at the end of a face to face consultation. Some problems only manifest themselves during real human interaction, a fact that is well understood by most therapists.

A woman with inoperable lung cancer has said she might have been treated sooner if she had received a face-to-face health assessment. After contracting Covid-19 in late 2020 she felt unwell. Her breathlessness and fatigue were put down to Long Covid. She was referred to a Long Covid service and attended virtual sessions by early 2021. Her lung cancer was diagnosed in early 2022.

Some clinicians adapt well to online and telephone consulting. They prefer the flexibility it offers, working anywhere and any time, tailoring work around lifestyle and family commitments. Once remote consultation became embedded and familiar, it was a natural step for some to look for better paid opportunities for remote working outside the NHS. So rather than solving the NHS crisis, it was made worse, in primary and secondary care.

Single issue private clinics mushroomed in the pandemic, offering assessments and recommendations for problems such as menopause, ADHD and autism. This enabled patient customers to bypass ever-growing NHS waiting lists, in pursuit of a diagnosis and/or recommendation for treatment. Invariably, these consultations would yield a pharmacological solution, which not uncommonly came as a recommendation for tailored off-license drug regimes and a request the NHS GP to take responsibility for prescribing. In May 2023, an undercover BBC investigation exposed serious concerns about ADHD clinics carrying out unreliable online assessments, leading to incorrect diagnoses and inappropriate recommendations for powerful medications. For some of our patients, these drugs have triggered psychosis and other serious morbidity.

Zoom and Microsoft Teams

It wasn’t just remote consulting that some of us found stressful. Workplace team meetings were also now conducted online, via Teams. The novelty of remote meetings soon wore off when people learned they could be simultaneously connected and disconnected: cameras turned off, leaving the speaker with the disconcerting experience of talking to a wall of initials. Decisions were rarely finalised, especially when people multitasked, walked their dogs or painted their nails.

Red Zones

For patients who needed to be seen face to face, there was a need to separate those most likely to be contagious from other patients. ’Red zones’ were quickly established, and dedicated clinics set up to care for people with suspected Covid-19 infection, to be kept separate from non-Covid patients who would be assessed in Green zones. Finite resources were unevenly distributed in expectation of a tsunami of potential ‘Red’ patients. There was a move to try to make General Practices dedicated ‘Green’ pathways, removing GPs from the Covid-19 assessment and diagnostic process. Anecdotally we heard that things could be very bad at the ‘sharp end’ in secondary care, but we also heard consistent reports of healthcare workers across the NHS finding themselves unexpectedly quiet, with spare clinical capacity for months at a time.

Soothed by Ritual

As new variants emerged, the symptoms of potential Covid became legion. So too did the recommendation to expand the number of Covid-19 screening questions which we were supposed to ask all patients before granting them entry to the building. By this point, the screening questions and their responses had already become so automatic, formulaic and overfamiliar, they had ceased to be effective at provoking cognitions. Some had distilled the screening to a single question, ‘Do you have any Covid symptoms?’, which was equally ineffective, but quicker.

After the initial turmoil of overnight organisational change to make the NHS ‘Covid-ready’, healthcare staff settled into the ‘new normal’ rhythms. Daily infection-control rituals helped to contain staff anxiety about the virus and imbued a sense of security. But after the first wave of infection subsided, there remained a general unwillingness across health and social care to re-evaluate the risk-benefit of actions taken and an almost superstitious reluctance to drop any of the safety measures.

When the dreaded apocalypse failed to materialise, this reinforced the post-hoc belief that our collective actions had succeeded in forestalling disaster (it would have been much worse…). Institutional rigidity prevailed and Covid-19 mitigation measures carried on for far longer than may have originally been envisioned at their initiation. From within certain Zero-Covid social media echo chambers, some doctors embraced the changes and even articulated an imagined future with zero institutional tolerance to any risk of viral transmission. At the extreme, such attitudes can resemble a neurotic aversion to the notion of ever again sharing air with germ-ridden strangers.

But risk is inherent in everything we do and all actions have unintended consequences. The focus on pre-symptomatic transmission had us all hyperaware of even the mildest of viral symptoms. A low threshold for testing led to more staff absences with ‘old normal’ common cold symptoms. In remote and rural areas, the turnaround of PCR testing was slow, so vital staff would be quarantined for days before getting the ‘all clear’ from a negative test. Parents were bound by the new rules to take frequent absences whenever their children had fevers. For most, this was a source of great frustration. But the opportunity to phone in sick, for real or imagined purposes, for moral or instrumental reasons, had never been more available to us.

If we quarantine asymptomatic healthcare workers on the basis of highly sensitive positive tests, we are stressing an already stressed system. This compromises safe staffing levels, leading to bed and ward closures, pressure on A and E, delays in ambulance response times, delays in treatment, cancelled appointments and increased morbidity and mortality. Did anyone measure the impact of the ‘Pingdemic’ on ambulance response times, health outcomes and hospitals being overwhelmed? And what about the staff being ‘side-skilled’, who were no longer doing the job that they were trained to do? What was the final humanitarian cost of refocussing resources in the way we did?