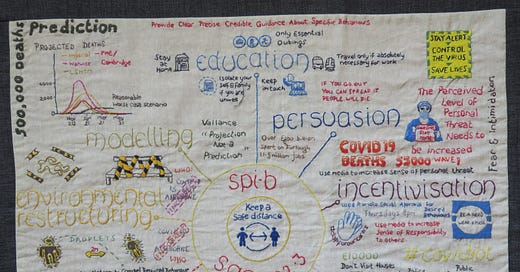

A week after Neil Ferguson’s team released their ‘Report 9’ recommendations for a lockdown suppression strategy, and just days before lockdown was announced, members of ‘Scientific Pandemic Insights Group on Behaviour’ (SPI-B), the behavioural-science subgroup of the Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE), convened at short notice to produce two papers for the government and wider SAGE committee.

The remit of SPI-B was ‘to offer government the best possible behavioural science advice to inform the response to covid-19, by providing ‘strategies for behaviour change, to support control of and recovery from the epidemic and associated government policy’.

The first paper, drafted by Professor James Rubin, looked at the current levels of adherence to the voluntary guidelines already put in place by the government at that time; the other, drafted on 22nd October by Professor Susan Michie, looked at all the options the government might want to consider in terms of ways of increasing adherence to general social distancing measures.

It is this second document that gained a certain notoriety over the course of the pandemic, as we began to experience myriad ‘spillover effects’ of the range of suggested strategies, some of them fatal.

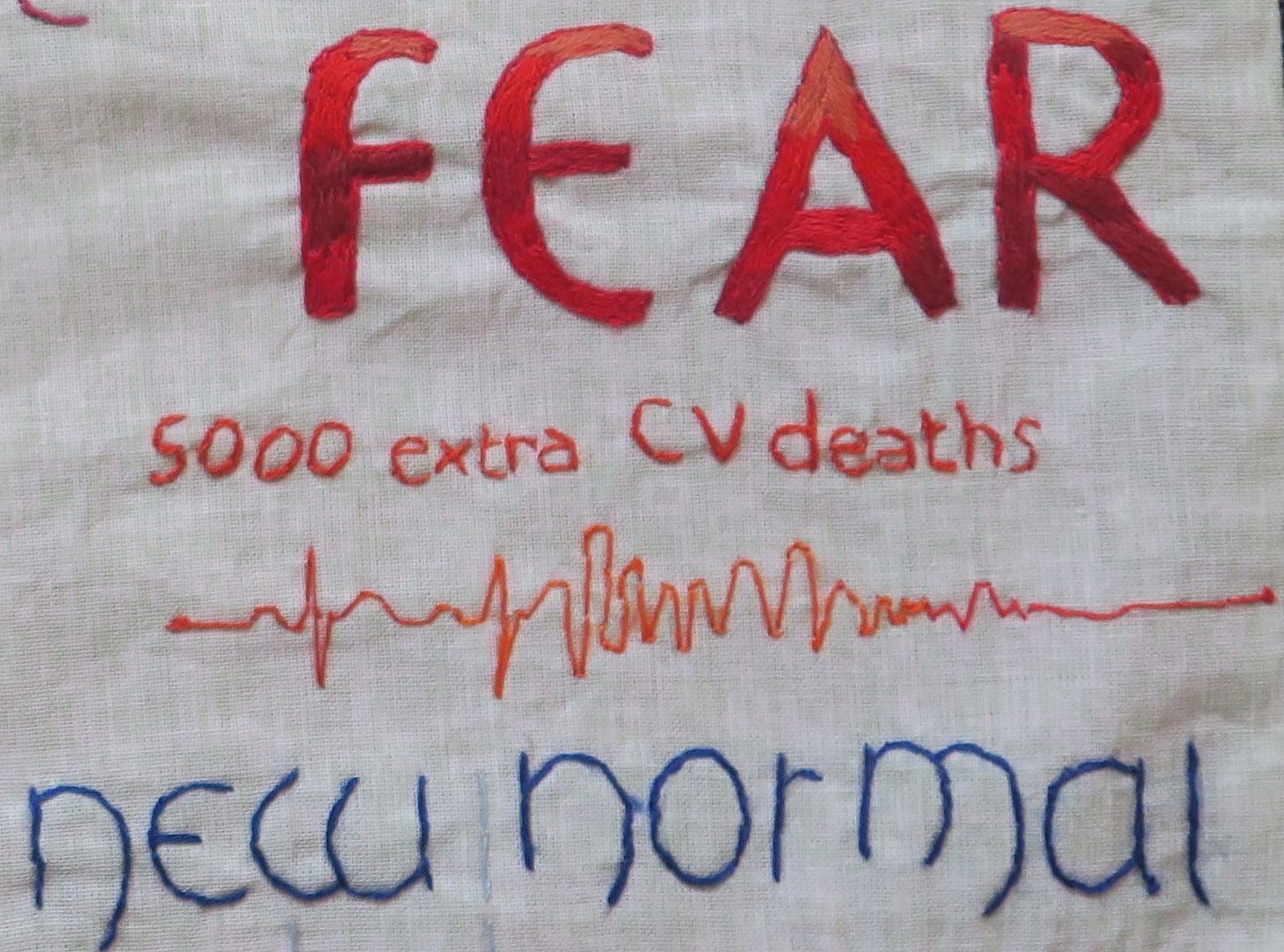

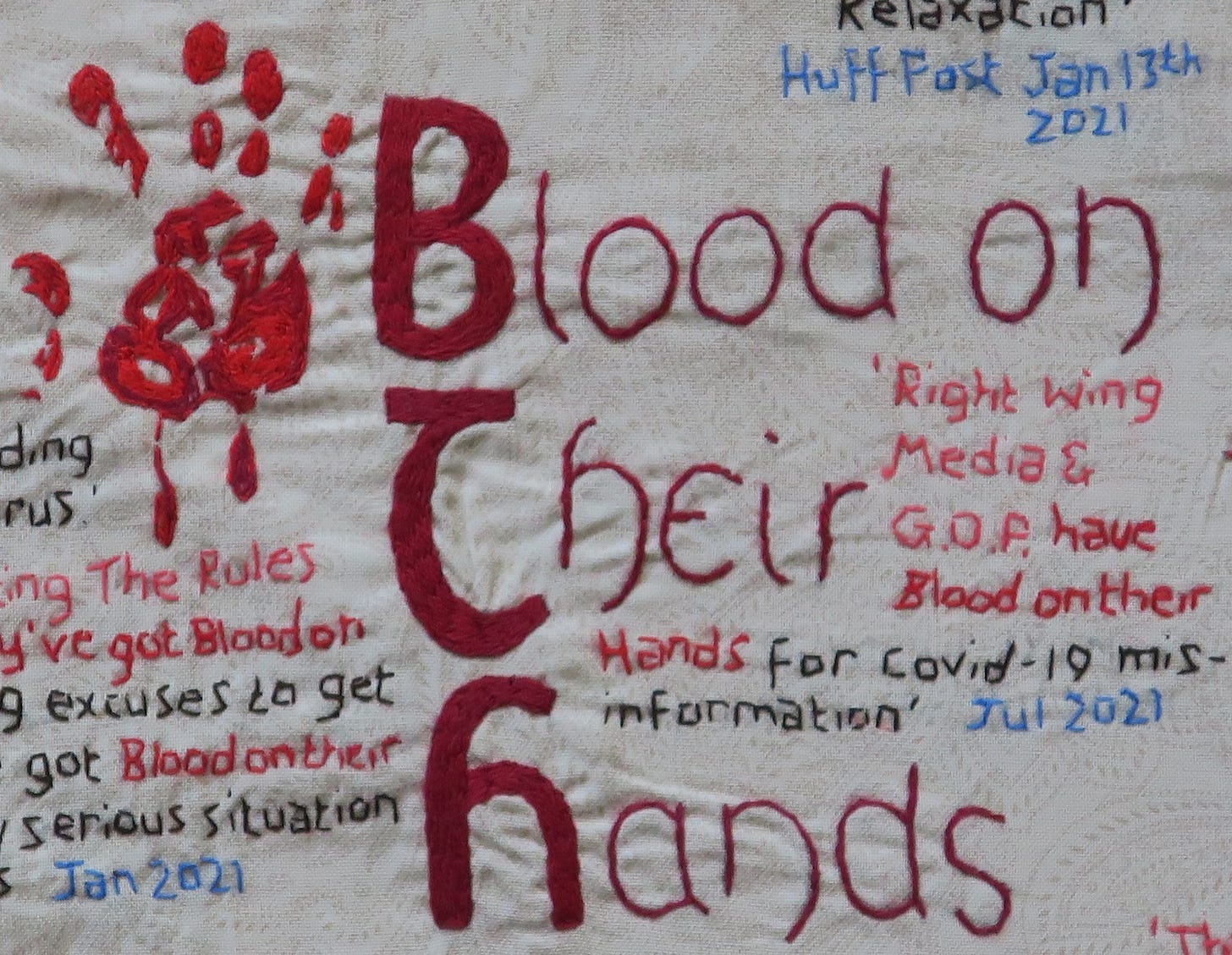

As it turned out, government communication about Covid-19 risk, channelled though the media, was indiscriminate and interwoven with propaganda, creating an overall climate of fear. Fear, shame and peer pressure became instruments for increasing public compliance, first with restrictive ‘non-pharmaceutical interventions’ (social distancing, lockdowns, masks) and later with vaccines.

Former NHS Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Dr Gary Sidley, has written about the British government’s ethically questionable use of behavioural science ‘nudge’ techniques throughout the Coronavirus pandemic. In January 2021, he and a group of co-signatories wrote to the British Psychological Society to raise their ethical concerns.

Sidley identified four groups of stakeholders who could feasibly be held to account for the use of covert psychological strategies to promote compliance in the pandemic: the British Psychological Society (BPS), the Behavioural Insights Team (government ‘nudge’ unit BIT), SPI-B and our elected politicians and their civil servants.

It seems that no one is now willing to accept responsibility for the fear-manipulating campaign and and the ramifications associated with it. Taking a position strikingly reminiscent of that taken by the SPI-M modellers, in a 2022 interview with the SPI-B co-chair, Michie’s 22nd March document is framed as merely a ‘presentation of the evidence base’ for techniques that could influence behaviour. In other words, despite being construed as such, it apparently was not a recommendation for guiding policy.

In March 2023, four SPI-B members submitted a BMJ opinion piece, ‘The UK government’s attempt to frighten people into covid protective behaviours was at odds with its scientific advice’, in which they exculpate themselves from the government’s use of fear in getting the public to comply with covid-19 restrictions.

Only one rapid response to this piece was published. One of the authors, Robert West, responds to what he describes as a ‘storm of accusations’ that they had been ‘trying to rewrite history’. Pointedly, he describes the Government’s pandemic approach as ‘authoritarian, fear-driven, scientifically illiterate, and contemptuous’, but apparently it was also ‘not based on advice we had given as contributors to SAGE through SPI-B’.

A number of SPI-B members did have major misgivings about the group’s influence and recommendations. In her book, A State of Fear: how the UK government weaponised fear during the Covid-19 pandemic, investigative journalist Laura Dodsworth quotes an anonymous SPI-B scientist,

‘In March [2020] the Government was very worried about compliance and they thought people wouldn’t want to be locked down. There were discussions about fear being needed to encourage compliance, and decisions were made about how to ramp up the fear’. They described their use of fear as ‘dystopian’ and ‘ethically questionable’, and went on to say that, ‘It’s been like a weird experiment. Ultimately, it backfired because people became too scared’.

According to Dodsworth, SPI-B member and educational psychologist Gavin Morgan, apparently expressed the view that his colleagues ‘went overboard with the scary message to get compliance’ and confirmed there was ‘no exit plan from the fear narrative’. Another member said they were ‘stunned by the weaponisation of behavioural psychology’ during the pandemic, and that ‘psychologists didn’t seem to notice when it stopped being altruistic and became manipulative. They have too much power and it intoxicates them.’

Evidently then, behavioural psychology was ‘weaponised’ in the pandemic. Though we now see behavioural scientists and the nudge unit representatives distancing themselves from the use of these techniques, at least in their crudest political forms, it is worthy of note that none of these professionals spoke up about their concerns at the time.

Will we ever discover how and why our government decided to use ethically questionable techniques to scare us into compliance, or is this destined to be another example of floating responsibility?

At the Hallett Inquiry, Professor James Rubin draws a clear distinction between SPI-B’s role in looking at ‘the science of communication’, and other groups he names who were working on the ‘operationalisation’ of this science: teams within the UKHSA (formerly PHE), the DHSC communications team and the Cabinet Office communications team.

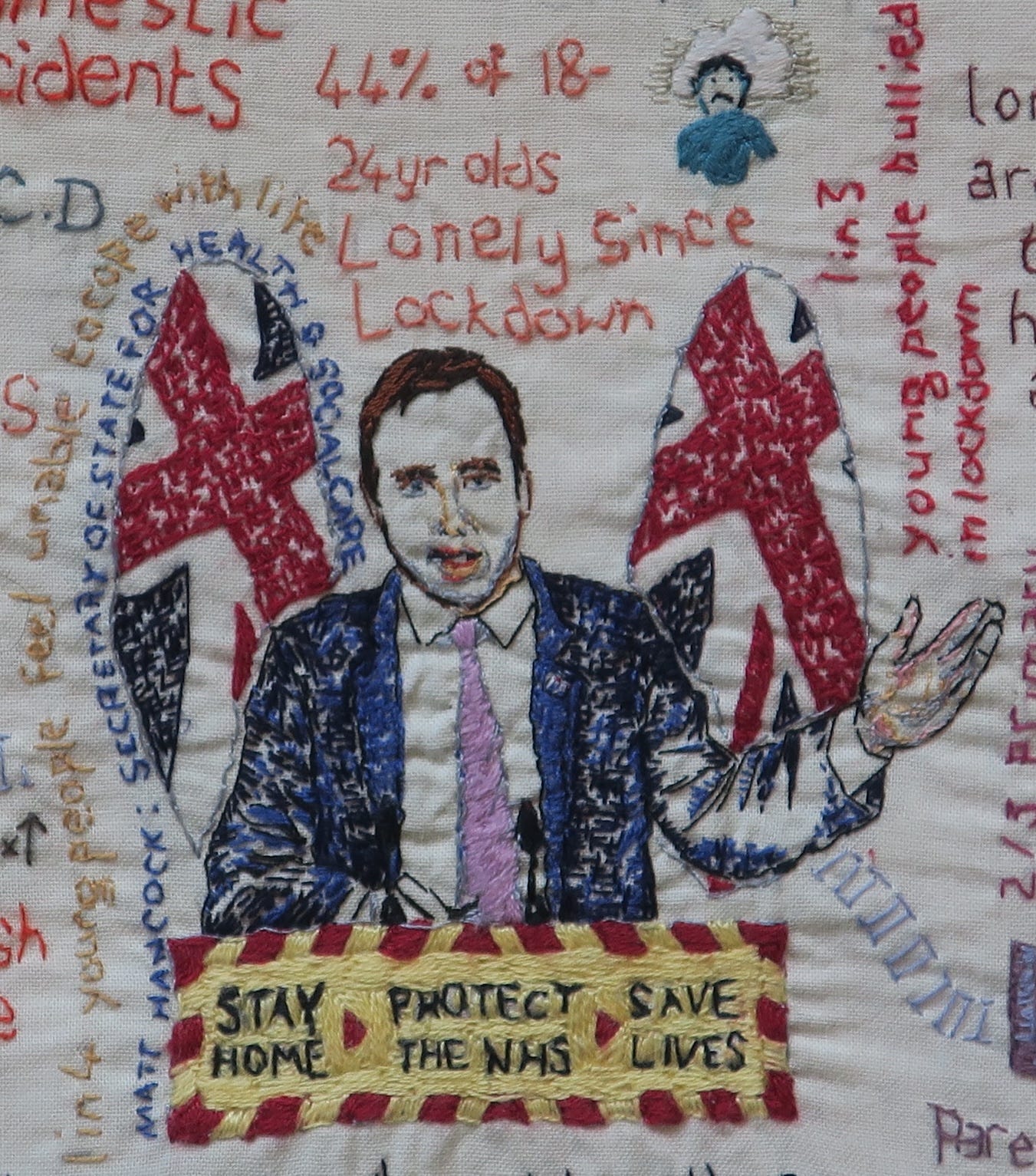

It is to the ‘operational’ side of government comms that our attention is drawn, with the sensational release of ex-health minister Matt Hancock’s December 2020 WhatsApp exchanges with his media adviser Damon Poole:

Hancock: “We frighten the pants [off] everyone with the new strain”

Poole: "Yep that's what will get proper behaviour change”

Hancock: "When do we deploy the new variant?” (referring, one assumes, to the Alpha variant).

In a separate exchange over what activities should or shouldn’t be prohibited in the proposed tier system, then UK Cabinet Secretary Simon Case remarked, “I agree -- I think that is exactly right. Small stuff looks ridiculous. Ramping up messaging -- the fear/guilt factor vital."

The condescending and flippant attitude Hancock and his ilk have shown towards the public gives us a focus for blame. But in our outrage at their behaviour, it is all too easy to overlook the fact that all the devolved governments settled on virtually identical Covid-19 suppression strategies and comparable fear and shame-based media public health campaigns.

Even if we take it at face value that Michie’s ’Options for increasing adherence to social distancing measures’ document has been misinterpreted and misunderstood, to outward appearances it does closely mirror strategies employed by UK governments. As such, it does provide a useful framework for considering the un-modelled and unmeasured ‘spillover’ collateral harms caused by lockdowns and the pandemic response structure. This is a subject I will attempt to cover in the following Substack chapters.

You are not going to believe this..

Next week at the London Vet Show Susan Michie will give a speech on how human behaviour change can be used to benefit animal and environmental health.

I am fuming. This is the woman responsible for the unethical fear mongering during the Covid saga.