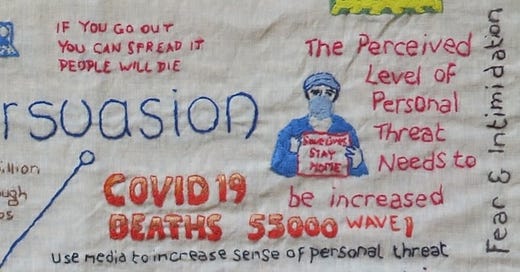

Perceived Threat

Perceived threat: A substantial number of people still do not feel sufficiently personally threatened; it could be that they are reassured by the low death rate in their demographic group… The perceived level of personal threat needs to be increased among those who are complacent, using hard-hitting emotional messaging. To be effective this must also empower people by making clear the actions they can take to reduce the threat.

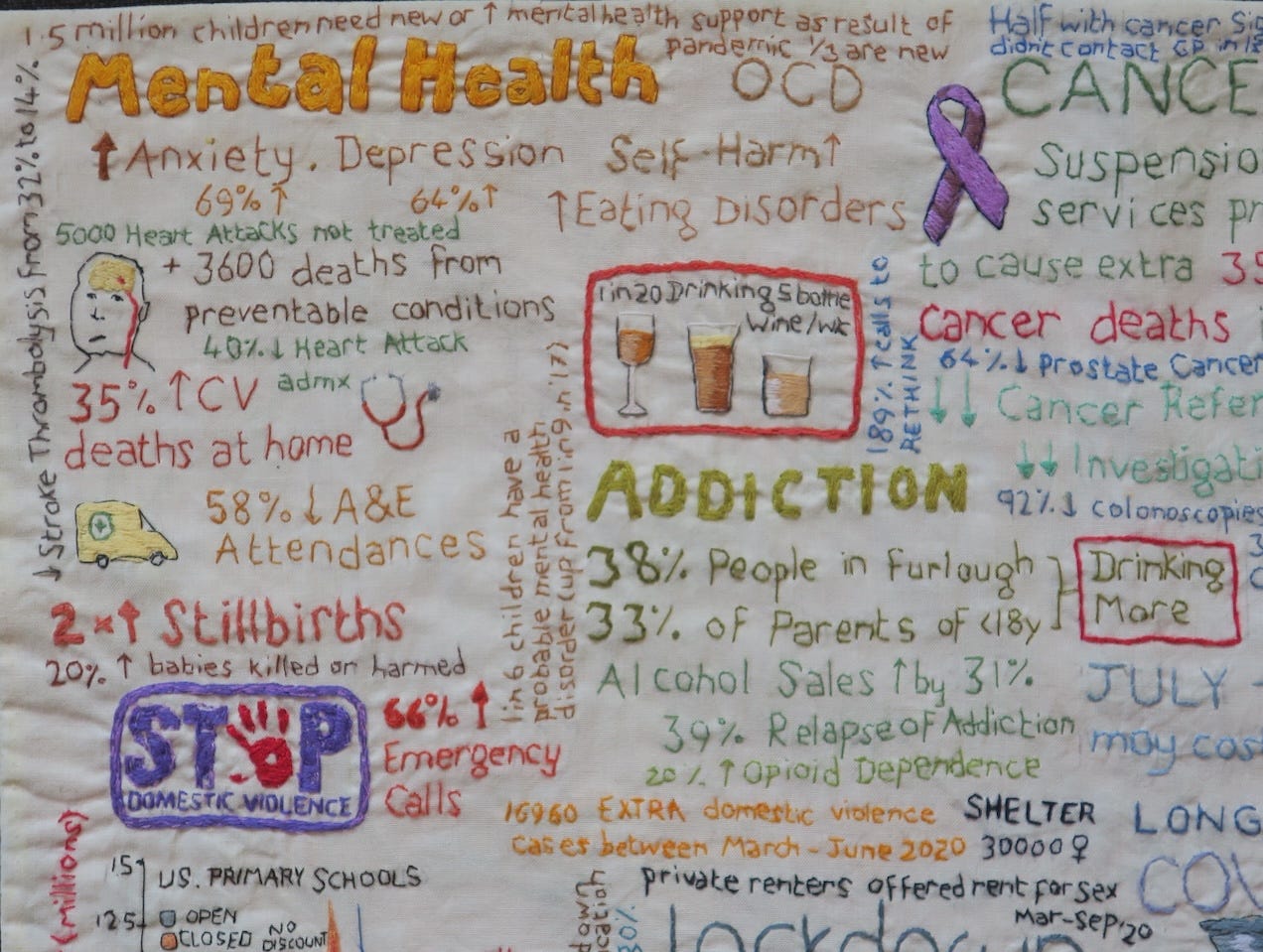

The government fear campaign was so effective that before long, people did feel personally threatened, and their perceived level of personal threat often bore little or no relation to the risk in their demographic group. They presented with symptoms of anxiety, panic disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder, depression, agoraphobia, loneliness, paranoia and even psychosis. Anxieties were reinforced by the social media accounts of vocal medics, and by frightening stories in the national press. Even fit and healthy young people didn’t feel safe enough to return to work after lockdown ended, and asked to be signed off sick, citing mental health.

Things were far far worse for the ‘Clinically Extremely Vulnerable’ who had endured months in isolation to contemplate their extreme clinical vulnerability and worry about the virus 'out there'. Released from shielding, some visibly shook with fear on leaving the house. Others needed counselling and are still suffering 3 years on, no matter how many vaccines and Covid infections they have endured. Shockingly, one study from Swansea reported no evidence that shielding benefited the vulnerable during the pandemic, with no impact on infection rates in that group of people.

For some, lockdown was a hell they couldn’t escape from. For others, lockdown and furlough was a cherished time spent with family; a time for creativity, leisure and a guilt-free release from social obligations, a time of virtue or sanctimony. This created jealousies and resentments amongst workers, especially those who believed they should have been furloughed too.

Working from home wasn’t always all it was cracked up to be either, with the boundary between work and home life blurred. People were lonely and missed the craic of the office. Sometimes the office wasn’t there any more, as enterprising employers had realised the energy cost savings to be made with the new Covid safety model, whilst serendipitously offsetting their business carbon footprint and boosting their Green credentials.

Responsibility to others

‘Responsibility to others: There seems to be insufficient understanding of, or feelings of responsibility about, people’s role in transmitting the infection to others. This may have resulted in part from messaging around the low level of risk to most people and talk of the desirability of building ‘herd immunity’. Messaging needs to emphasise and explain the duty to protect others’.

Some, myself included, consider ‘Stay Home, Protect the NHS, Save Lives’ to have been the most unsettling public health campaign since the ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’ AIDS campaign in the 1980s. But this was just a warm up for what was to come. In September 2020, Scottish government released a sinister advert, complete with horror movie soundtrack, depicting a young woman contaminating her grandfather’s kitchen in green Covid slime whilst making him a cup of tea. The video purports to be sharing a helpful reminder of ‘the rules’ to keep grandad safe. The guilty granddaughter had recklessly broken ‘the rules’ by partying with friends and we all knew how that story ended.

‘The rules’ were arbitrary and bewildering and kept changing. At that time they stipulated only 6 people from a maximum of 2 households were allowed to meet outside, and they must stay 2m apart. There would be new harsher punishments for those who did not comply. Police were given the power to arrest miscreants and issue fines of up to £960 for repeat offenders, or up to £10,000 for those who refused to pay. 10pm curfews were imposed on pubs, bars and restaurants, with warnings of harsher punishments if the rules were broken.

Like the tombstone and iceberg AIDS public health ads of the 1980s, the Scottish ad was aimed at two groups of people – those suspected of ‘bending the rules’ and those who ignored them because they did not believe they were at risk. I don’t know whether such a campaign would influence behaviour as intended, but it would likely inflict the most psychological harm on people who were already compliant and afraid.

Not to be outdone by Scots, the British Government launched an even more stigmatising ad campaign in January 2021, a few weeks into the third national lockdown. "Can you look them in the eyes?" featured close-up facial shots of of doctors, healthcare workers and COVID patients wearing oxygen masks, asking people if they can "look them in the eyes" and tell them they are doing everything they can to stop the spread of the virus, urging the public not to leave home unless for essential reasons.

The intention was to guilt-burden and shame people into compliance. Rule breakers were characterised as selfish, dim-witted ‘Covidiots’, with even more discriminating labels applied on social media. Some people did openly reject the authoritarian approach to Public Health but in reality, the confusion of rules allowed even the average conformist some room for comical interpretation or a degree of plausible deniabilityy, should they be caught in a misdeed.

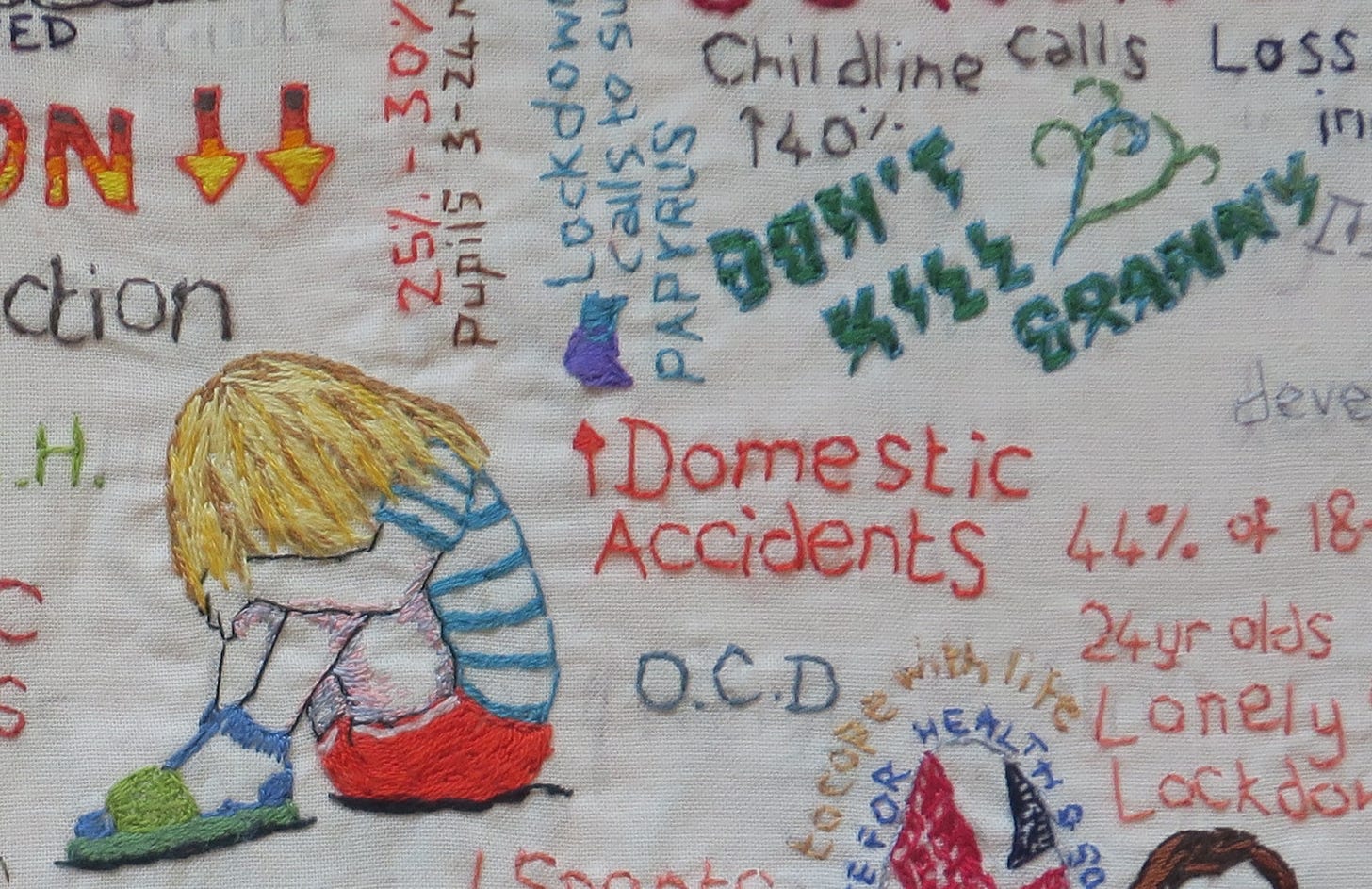

Mass behavioural modification can of course be justified in terms of benefit for the greater good (nudges), but that does not mean individual harms should be ignored. In 2020, I became increasingly concerned about the adverse impact of the Public Health information campaign on the mental health of the population, especially young people. The ‘don’t kill grandad’ video did not add to public knowledge and understanding about the risks of the virus, but did have the potential to psychologically harm children.

Professor Sunetra Gupta has been forthright in her criticism of such methods,

“Telling a child that they might kill their grandma just by having given them a hug is a complete dereliction of our duty towards them. It is also a violation of the unwritten contract that protects the individual from bearing the guilt of the inevitable harms (such as the spread of disease) that arise from living collectively in a society.”

One forensic psychologist pointed out the obvious potential ramifications of the new advert, ‘Just imagine if a child had a grandparent who they were hugging and then a few days later that grandparent died. Whether that is COVID-19-related illness or not, they will live with that forever.’

We were already seeing patients who were terrified that they would be held responsible for the deaths of their grandparents, parents reporting sleep disturbance and/or anxiety and behavioural changes in their children. Children were being referred for counselling. Teachers were reporting increased anxiety in young pupils; some had developed a fear of going to school.

It was not only children who were affected. As Jefferson and Heneghan have pointed out,

‘Lockdowns act to normalise the risk across age groups, ensuring those most at risk of adverse events have the same risk as those with the least risk. For some, lockdowns provide a simple tool for a highly complex problem. But they meant that strategies were not deployed or trialled to protect the most vulnerable. Lockdowns are alluring because they offer a simple message: staying home will protect you. But does it?’

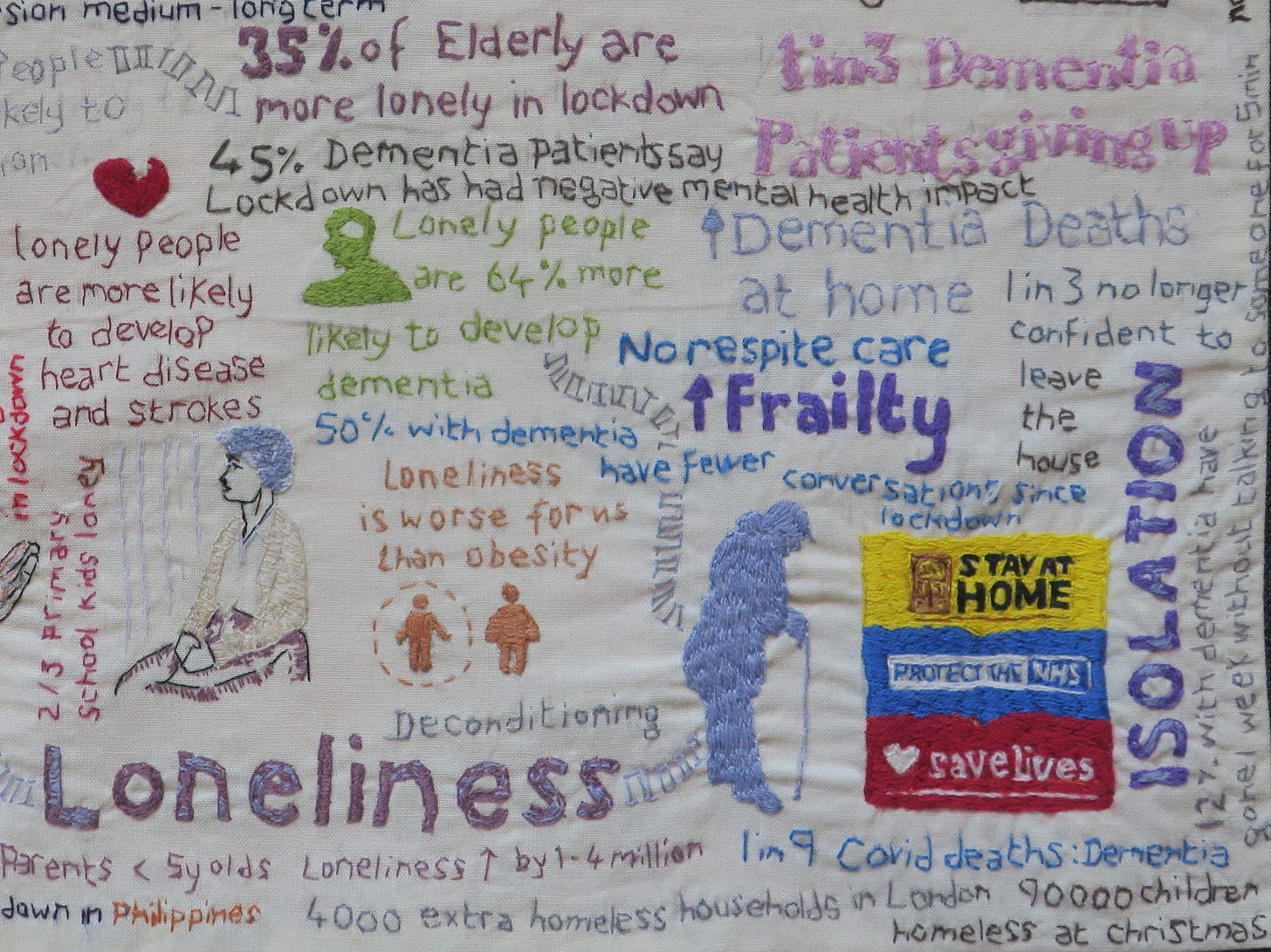

Lack of physical activity in the elderly led to increased frailty and increased chronic pain symptoms, ironically increasing susceptibility to more severe illness and reducing life expectancy. Without family visits, older people deteriorated physically and mentally. They became depressed and isolated, missing the contact with family that gave their lives meaning and value.

Researchers from Glasgow have since found that a lack of visits from friends or family is linked with an increased risk of dying. People who were never visited by friends or family were at a 39% associated higher risk of death compared with people who said they had daily visits. Those people who had visits from friends or family on at least a monthly basis had a significantly lower associated increased mortality risk, suggesting that there could be a protective effect from this social interaction.

Age UK’s advice line took an increased number of calls from older people who were acutely distressed, including some who expressed suicidal ideation. As a result, they had to provide additional training to their advice line call handlers. Some elderly people turned their faces to the wall, withdrew from life and prepared to die. In hospitals, without visitors, I heard reports of ward patients who had simply lost the will to live.

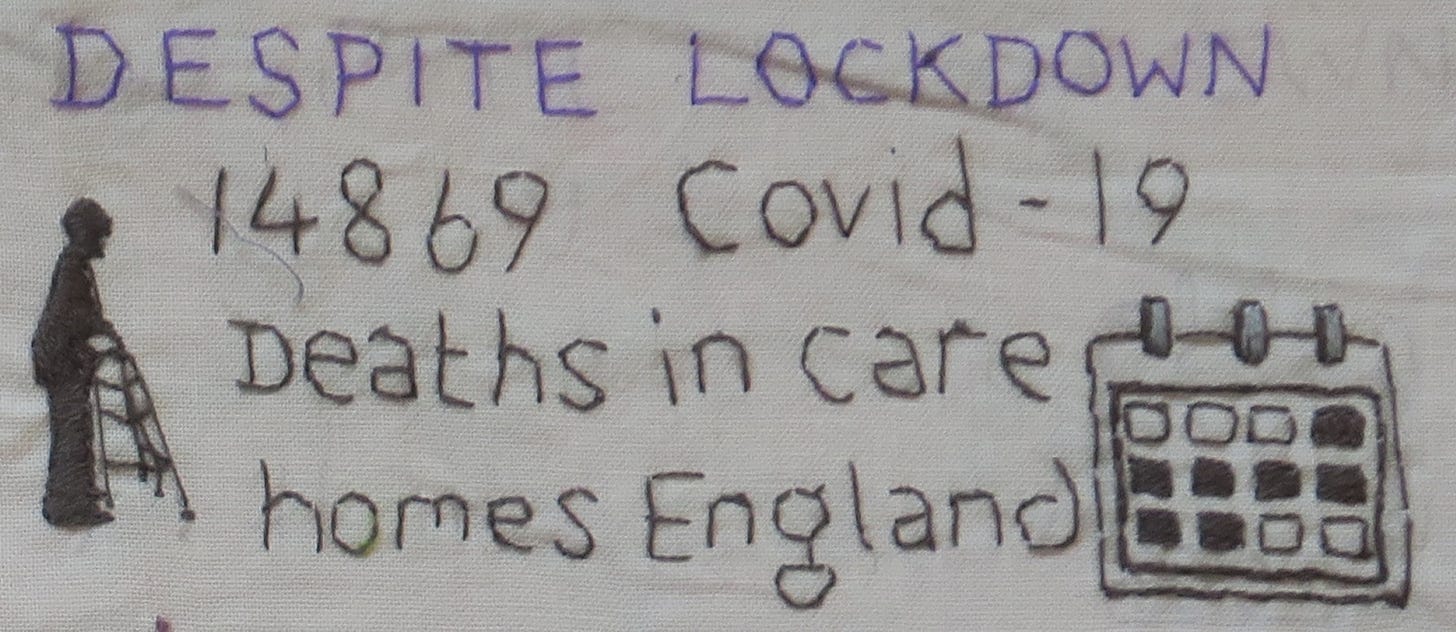

Finally, we should not lose sight of the fact that ‘lockdowns’ didn’t actually help the care homes, which accounted for almost half of national Covid-19 mortality.