The Forgotten Carers

A report from the National Children’s Bureau in Northern Ireland found that families of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) felt they were “forgotten" in the response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Carers were cut off from support services as their children struggled to cope with the ‘New Normal’.

Risk assessments linked to Covid-19 had been used by some schools to prevent SEND pupils attending. Service providers struggled to evaluate the net balance of risks, with little consideration apparently given to the negative health consequences of stopping services. Remote learning for children with SEND was extremely challenging, if not impossible.

School closures disrupted essential therapies like speech and language therapy, occupational therapy and physiotherapy. Parents reported regression in their children due to the withdrawal of services. Day centres remained closed, even after other restrictions had been lifted and some were forced to close for good. Some carers felt that Covid-19 was used as "an excuse" by these agencies to not provide services or to limit services.

A damning report by Ofsted and the CQC highlighted the cumulative effects of disruption caused by the pandemic on the health, learning and development of these children. Inspectors found that by Spring 2021, families were exhausted, even despairing, particularly when they were still unable to access essential services for their children.

The pandemic response led to a lack of respite care for these carers, and for carers of relatives with frailty and dementia, which could precipitate to crisis. In a survey by Mencap, over half of family carers of people with learning disabilities said that they had struggled to cope with supporting their loved one during the COVID-19 pandemic and three quarters reported a detrimental impact on their own mental health, relationships and physical health.

This chronic stress would leave carers feeling at ‘breaking point’ and reduce their resilience to illness. Some parents even considered suicide pacts, such was the level of their distress. Dylan Freeman, a child with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities, died at the hands of his mother. The judge in that tragic case concluded that Dylan should be acknowledged "as an indirect victim of interruption to normal life caused by the Covid-19 pandemic”.

At the 2023 Scottish Covid-19 Inquiry, a Scots mum described how her 39 year old daughter, who has learning difficulties, felt she ‘lost her family’ due to restrictions in care homes. A key factor in her physical and mental decline was not being able to see her family face-to-face until August 2020. Her daughter eventually began video-calling around five or six times each day in distress. She gained weight and stopped talking about the future. In a statement, she said,

“It feels like I’m a prisoner, and not able to do things like go out shopping with my mum…It’s hard to keep it together, and I’m not able to get cuddles from my family..I feel like I’ve lost my family. I would like to do something about it. I would like to tell somebody how I’m feeling; somebody in the government..I feel angry and fed up.”

Young carers faced increased caring responsibilities, lack of support from friends and wider family and a lack of respite. They described heightened anxieties and not being able to ‘get space’ to manage their stress. Some were struggling with home learning and described the practical barriers such as having to care for younger siblings or not having a quiet space for study. For many, the routine of school was their only respite from the burden of caring. Despite the difficult circumstances, many young carers felt unable to complain, as this could be construed as “selfish” and insensitive to the person they were caring for, to say nothing of the psychological effects in an atmosphere of public moral pressure to conform.

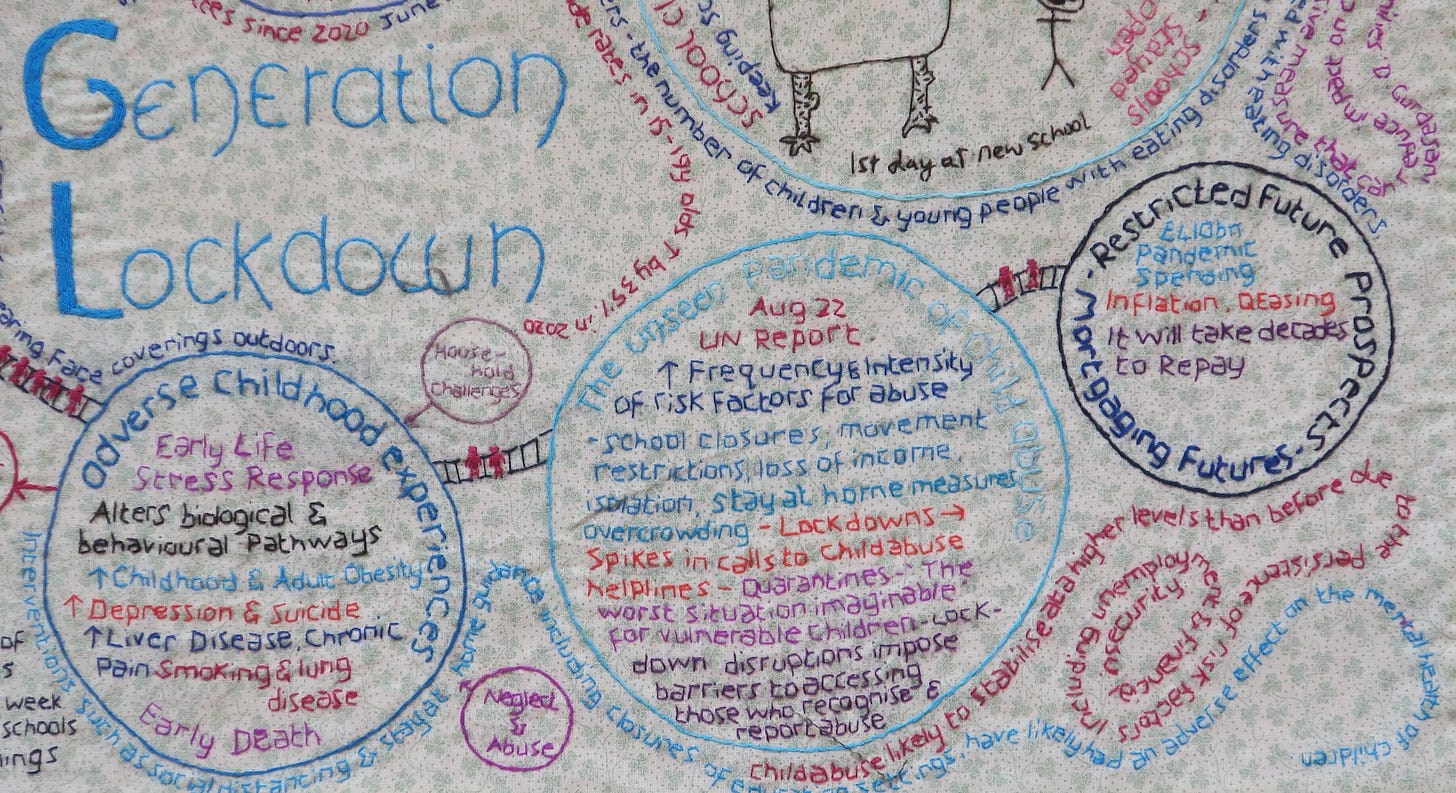

The Forgotten Children

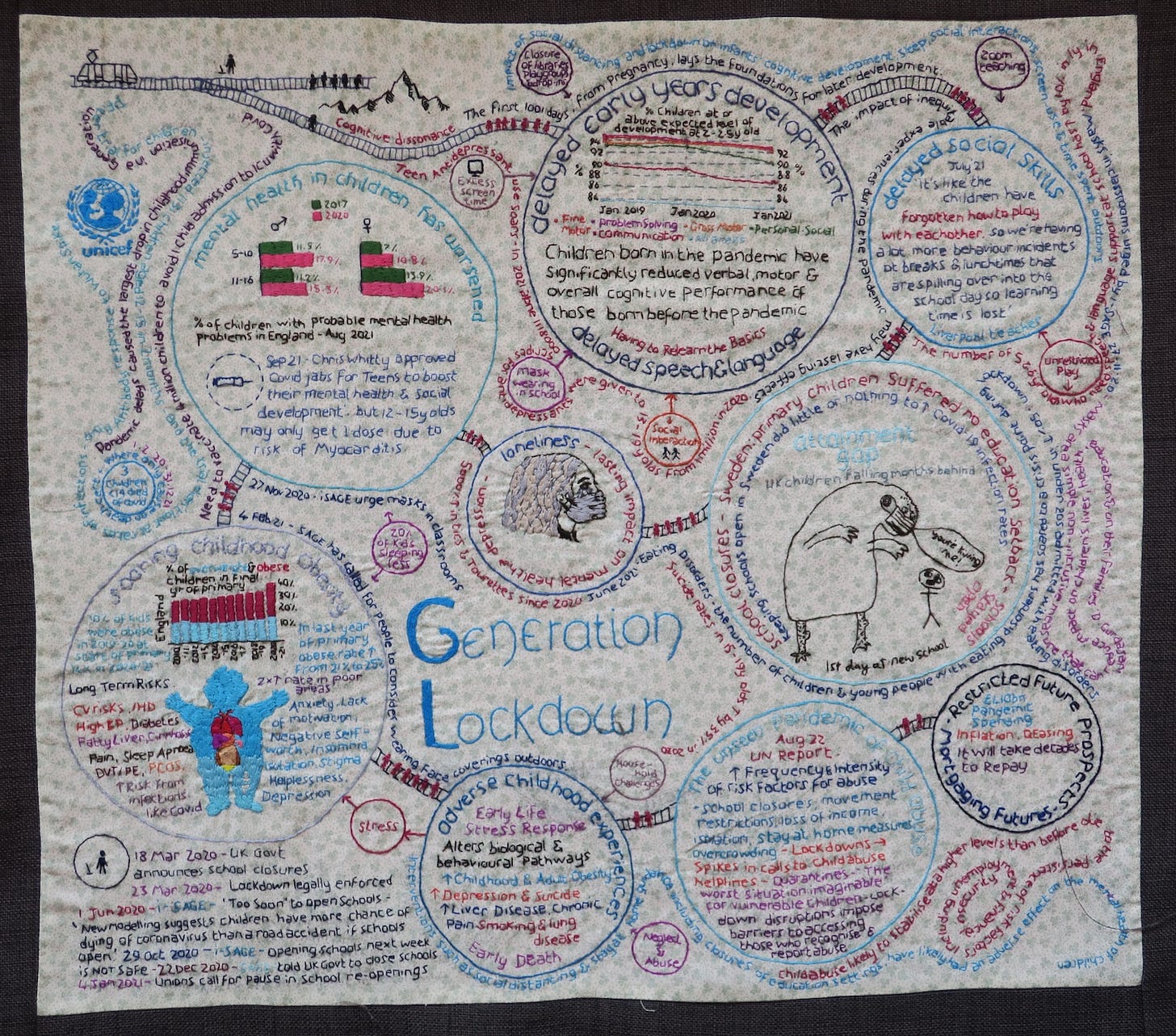

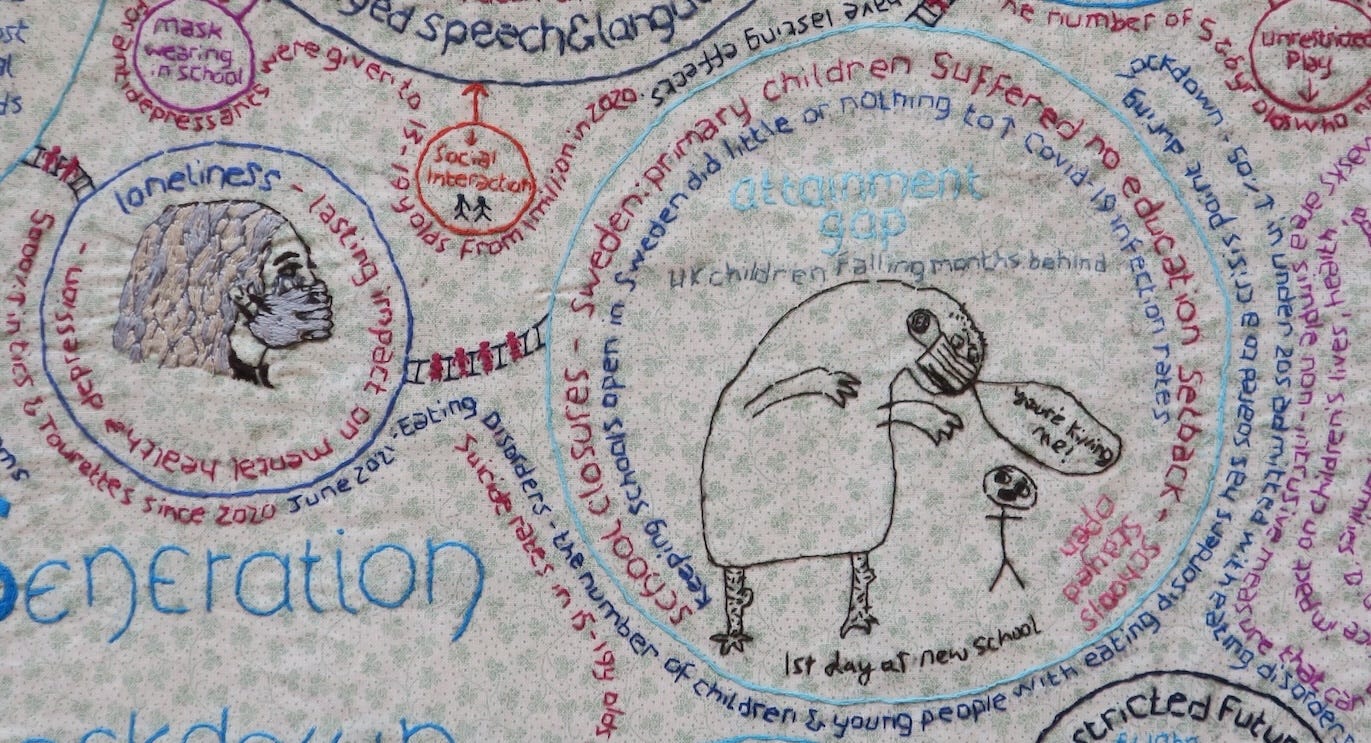

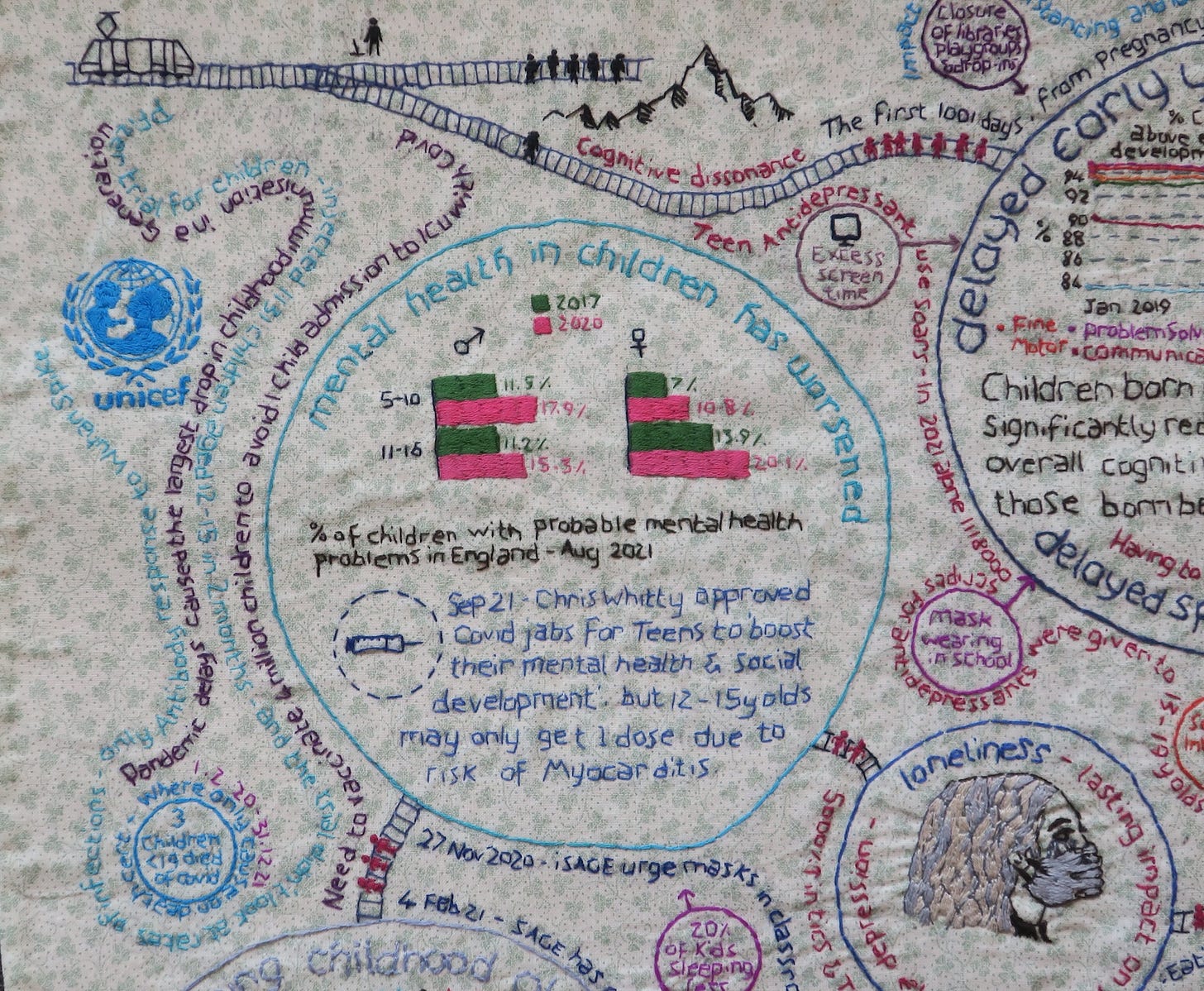

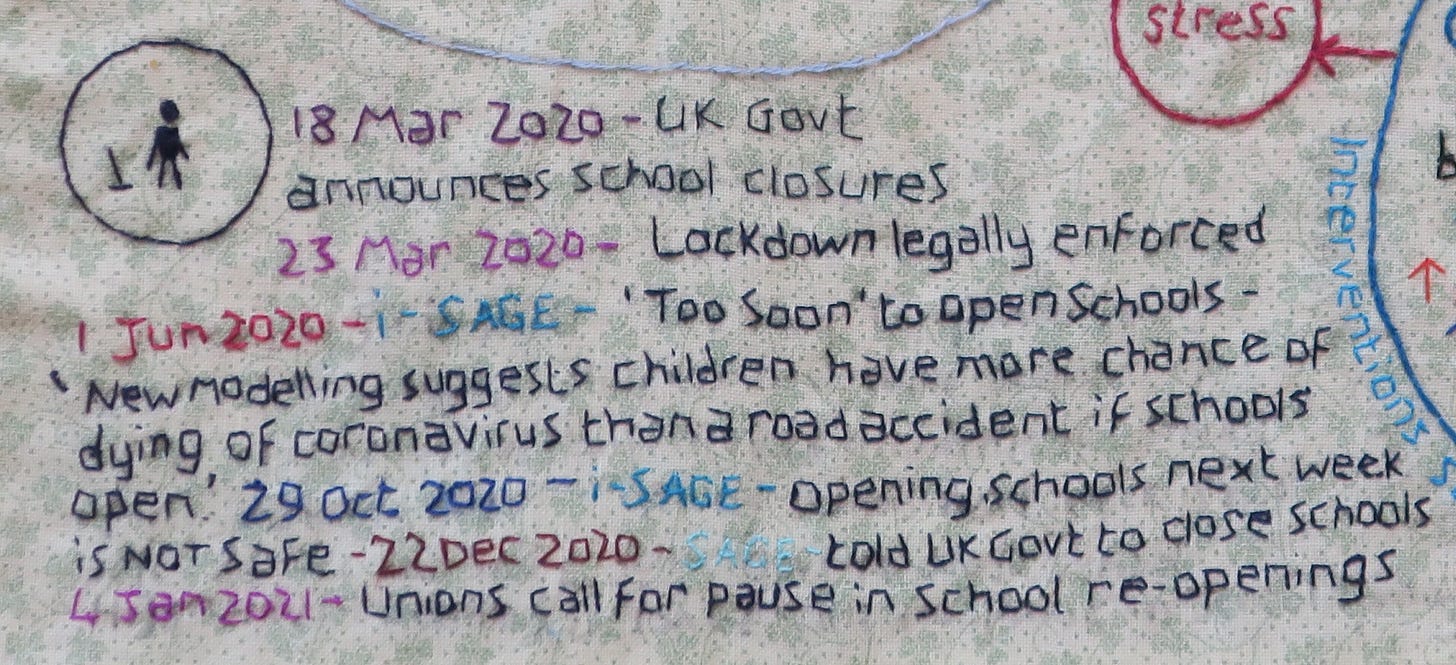

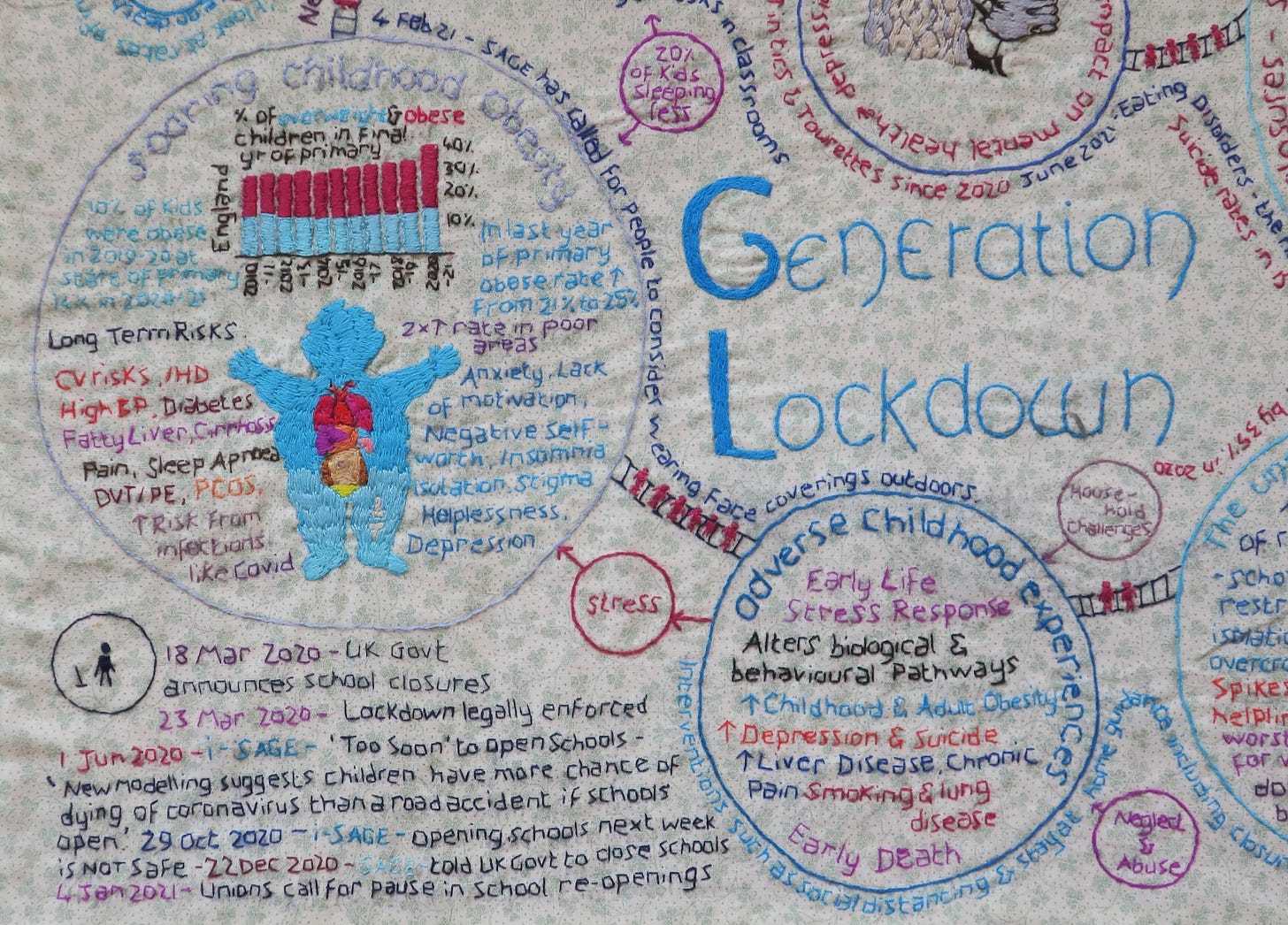

School closures, restricted social activities and parental anxiety impacted the mental health of children, disproportionately affecting those already disadvantaged. Higher levels of anxiety and behavioural problems were observed in children, alongside motor tics and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Triggers included loss of usual friendship contacts, anxieties about disrupted education and future prospects, anxieties about returning to school and loss of confidence in social interactions, anxieties about germs and dying of Covid and anxieties about killing family members, all fuelled by the unrelenting exposure to worrying government and media broadcasts.

The number of young people seeking help for mental health problems soared, jumping from an estimated 12.1 per cent of children in 2017 to 17.8 per cent in 2022, with the biggest increase seen in those aged between seven and ten. At the same time, young people were often unable to get support when they needed it, with lack of face to face appointments a further barrier to care. The number of under-18s getting NHS help for mental health issues in England nearly halved in the first two months of lockdown, with some parents resorting to private care where they could afford it.

In our surgeries we saw children with new eating disorders or a worsening of pre-existing eating disorders, triggered by loss of the usual coping mechanisms (friendships, school sports, clubs and other social activities), loss of structure and routine. A 2023 Lancet study confirmed that what we were seeing was being replicated across the UK, with lockdown seeing a staggering 42% rise in newly diagnosed eating disorders among teenage girls, with similar increases seen in self-harm. Researchers from Manchester University found that social isolation, anxiety from changing routines, more time exposed to social media, and disruption of education during lockdown appeared to have increased distress among teenage girls.

Local teachers observed a deterioration in the mental health of children on returning to school after lockdowns, and it was difficult to concentrate on educating children in these circumstances. A German study showed that children’s intelligence levels dropped when schools were shut down during the pandemic, but was unable to prove causality. The difference in performance between those from disadvantaged backgrounds and their better-off classmates widened significantly between 2020 and 2022. Some children got out of the habit of education and once schools reopened, many thousands of children failed to turn up.

A Toxic Mix: The Unseen Children

Early life stress (or toxic stress), including Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), poverty, inequality and poor access to healthcare and education are risk factors for disrupted neurodevelopment, leading to increased risk of impaired social, emotional and cognitive development, obesity, adoption of health risk behaviours, disease, disability, chronic pain, substance dependence, depression and early death.

There is little doubt that the decision to close educational establishments caused immeasurable harm. In spite of this, in 2021, the Scottish Government announced plans to introduce legislation to make some emergency Covid-19 powers permanent. This would include the ability to impose lockdowns and order school closures for any future outbreak of an infectious disease, so long as they believe it is "necessary and proportionate" and the chief medical officer has been consulted.

Predictably, no one now wants to claim responsibility for decision making. By June 2023, when the cumulative harms of the pandemic response had become impossible to ignore, reformed Zero-Covidian Devi Sridhar implored, ’don’t blame scientists for what went wrong with Covid – ministers were the ones calling the shots’.

Globalism's cry of ‘No one is safe until everyone is safe’, rings hollow when we hear of an alarming 20% rise in babies being killed or harmed in the UK during the first lockdown. A "toxic mix" of isolation, poverty and mental illness, exacerbated by Covid restrictions, led to the largest increase in serious incident notifications during the first half of 2020 (60 compared with 27 in the second half of the year).

When schools were closed, vulnerable children became ‘invisible’. The number of young children murdered in the UK almost doubled in a year as killings at home soared during the first lockdown. More than 220 children died through child abuse or neglect. Children like Arthur Labinjo-Hughes, who ‘suffered 'a bruise for every day of lockdown' at the hands of his cruel dad and step-mum’; Star Hobson, a toddler who suffered weeks of physical abuse before she was fatally assaulted by her mother's partner; 16 year old Kaylea Titford, a girl with spina bifida who suffered horrific neglect at the hands of her parents but remained "hidden from the world" because of the coronavirus lockdown; 5 year old Logan Mwangi, who was was murdered by his mother, step-dad and step-brother in lockdown - a report concluded that social workers had a "lack of confidence in challenging the family’s potential use of Covid 19 anxieties and Covid 19 symptoms as a barrier to engagement with services.”; 10 month old Finley Boden who suffered 130 injuries before his death at the hands of his parents, who used lockdown as a cover to prevent social services from visiting and Lola James, a toddler who died at the hands of her mother’s partner.

Born at the height of the pandemic, Jacob Crouch was murdered at 10 months by a brutal stepfather after enduring months of physical abuse. At the trial, Jacob was described as an ‘unseen child’ who was not being seen by social workers in person when many services were being held remotely.

In August 2023, after both parents had been sentenced, Detective Chief Inspector Bullock from Derbyshire Constabulary was asked about the increased risk of child cruelty for those born during lockdown. His reply: ’Hopefully this is the last one [we] will have to deal with.’