NHS leaders and senior managers were worried about our fragile health service becoming overloaded, were afraid of being held culpable for the deaths of healthcare workers and for vulnerable people contracting Covid-19 in NHS buildings. GPs shared these anxieties, but we also needed to remember our primary obligation, which was to continue providing good medical care to our patients.

As March rolled into April, four key themes emerged from the top-down information overload: Protection, Pre-emptive Planning, Triage (rationing) and Anticipatory Care/Shielding.

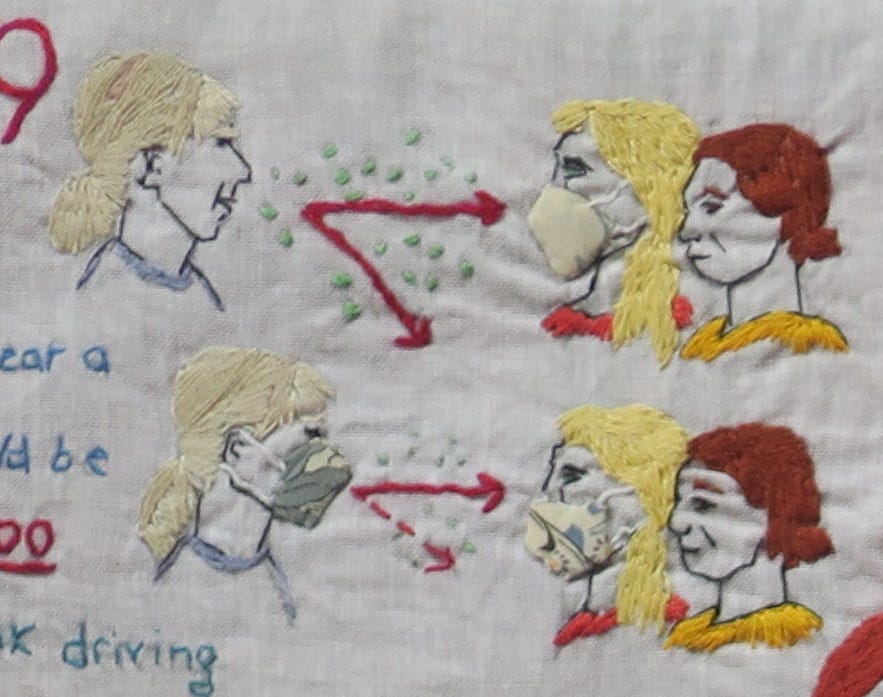

1. Protection from infection

Our early frenetic activity was hard to sustain in the face of no actual sign of the virus. Covid fatigue mixed with Covid anxiety, in a pressure cooker of emotion. There was no escape even outside the workplace. The media had started to report the UK Covid-19 death toll, by now in double figures. Those of us without televisions had partial immunity to the fear messaging.

For the first time in history, people were being paid to stay away from work, because the virus was so deadly. For those who carried on, this signified the inherent danger of the workplace, and heightened their own anxieties. Others amongst us felt relieved to at least have a sense of purpose and control.

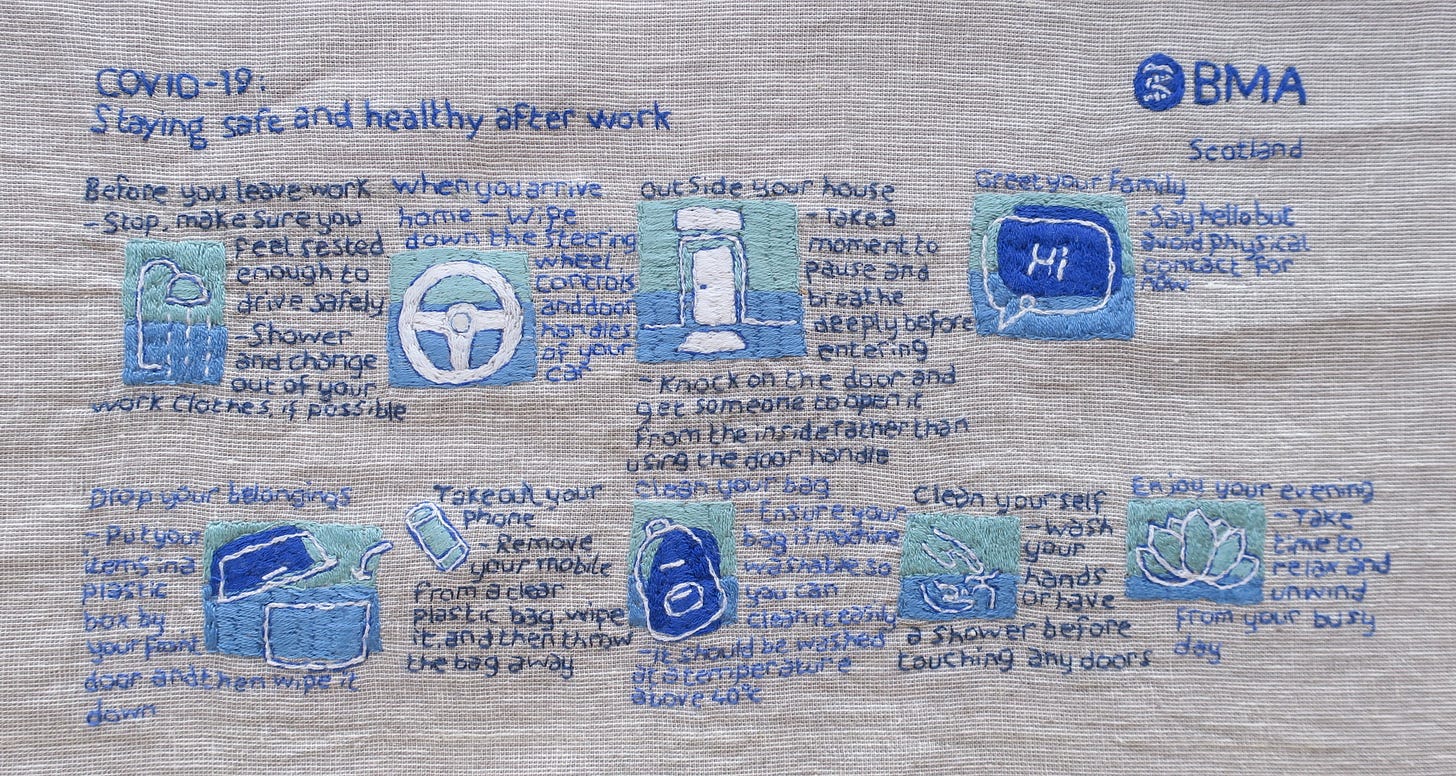

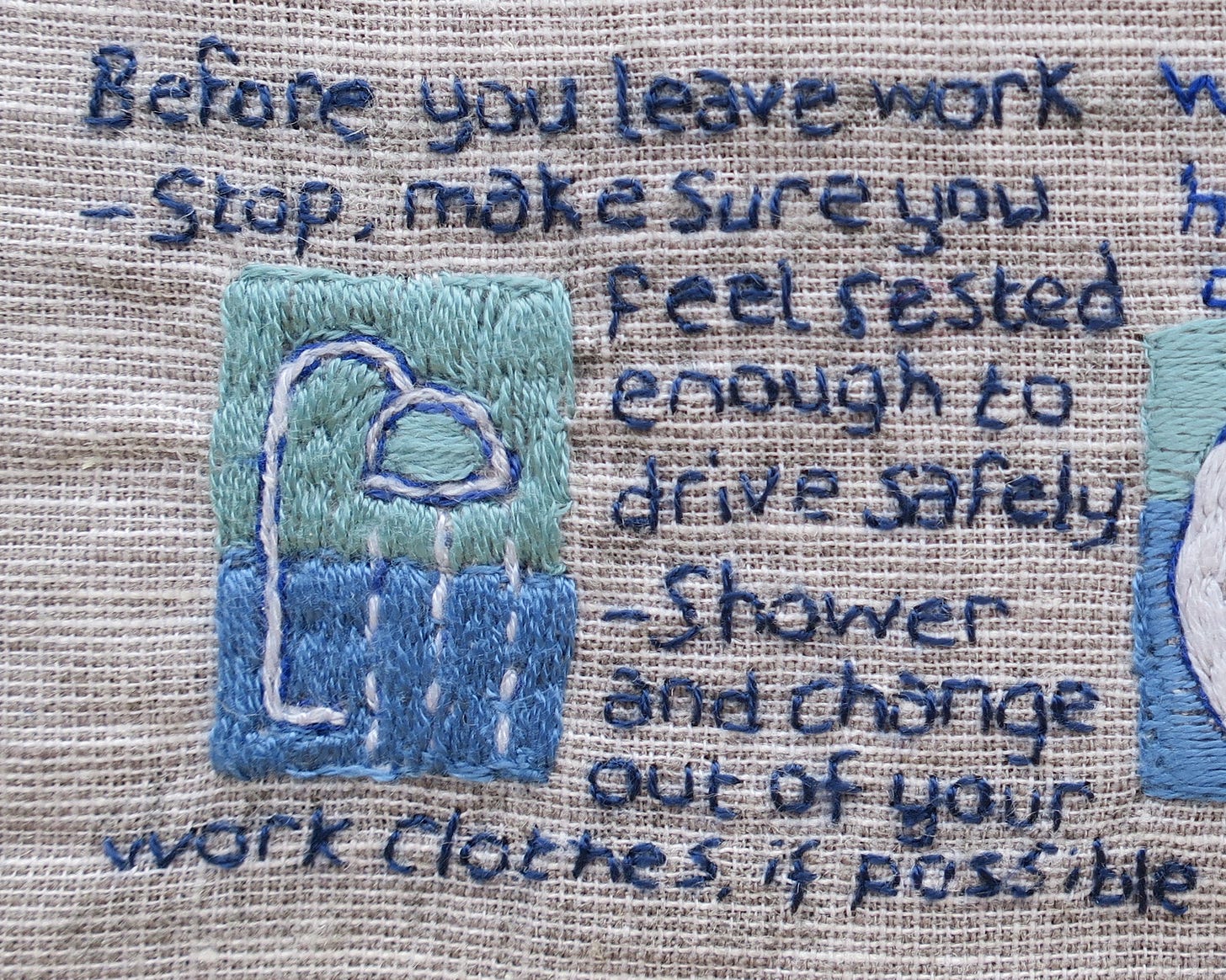

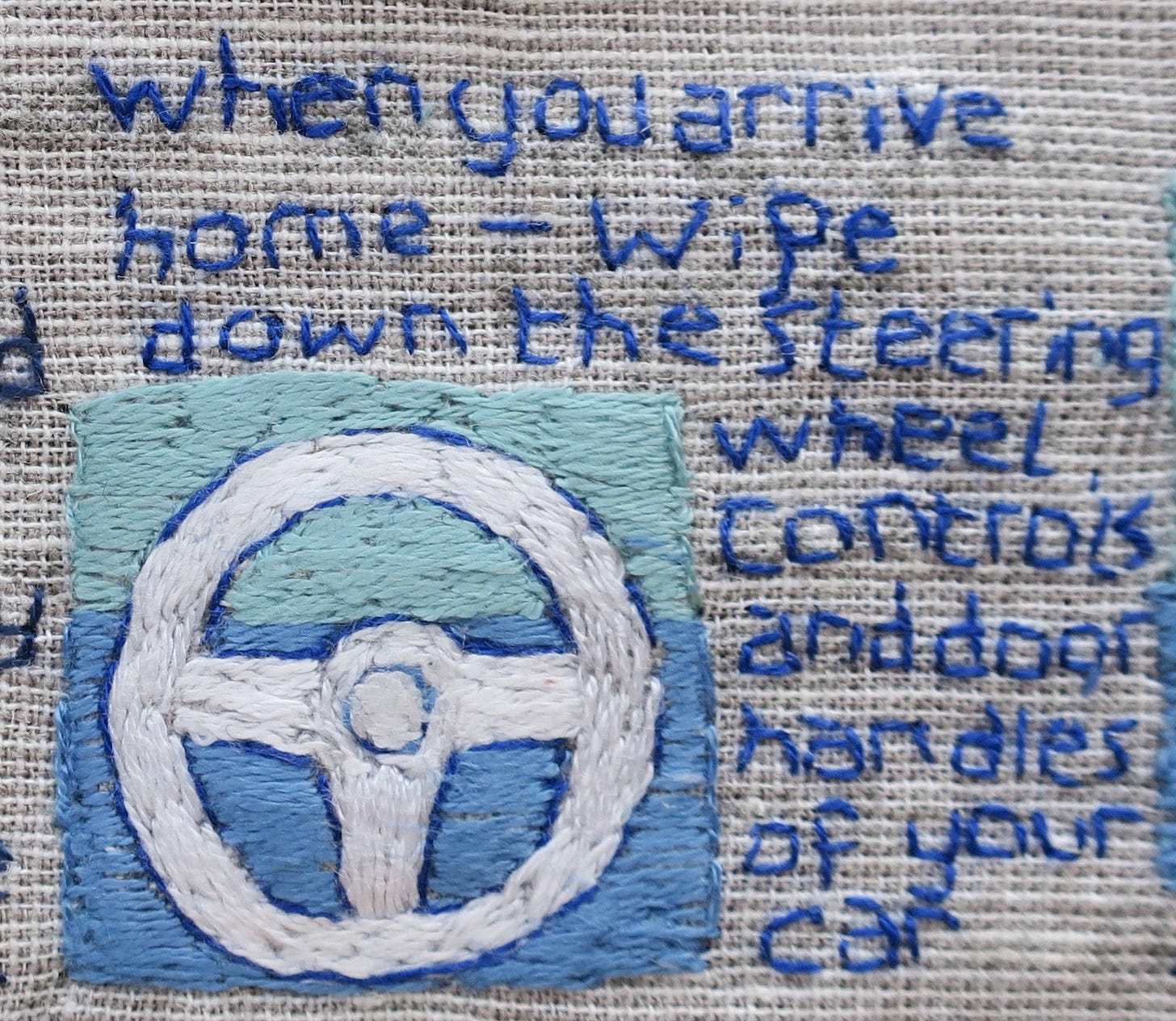

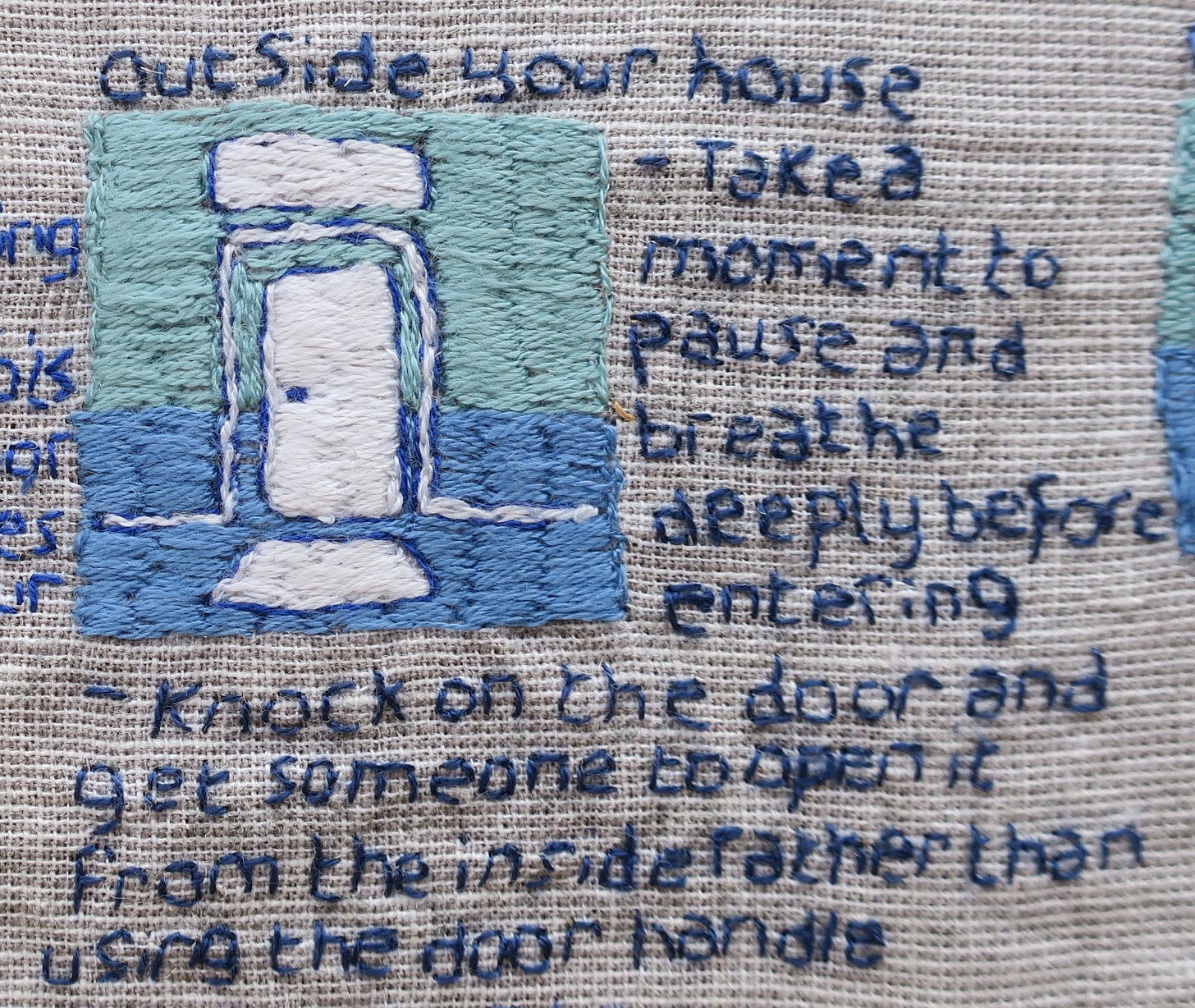

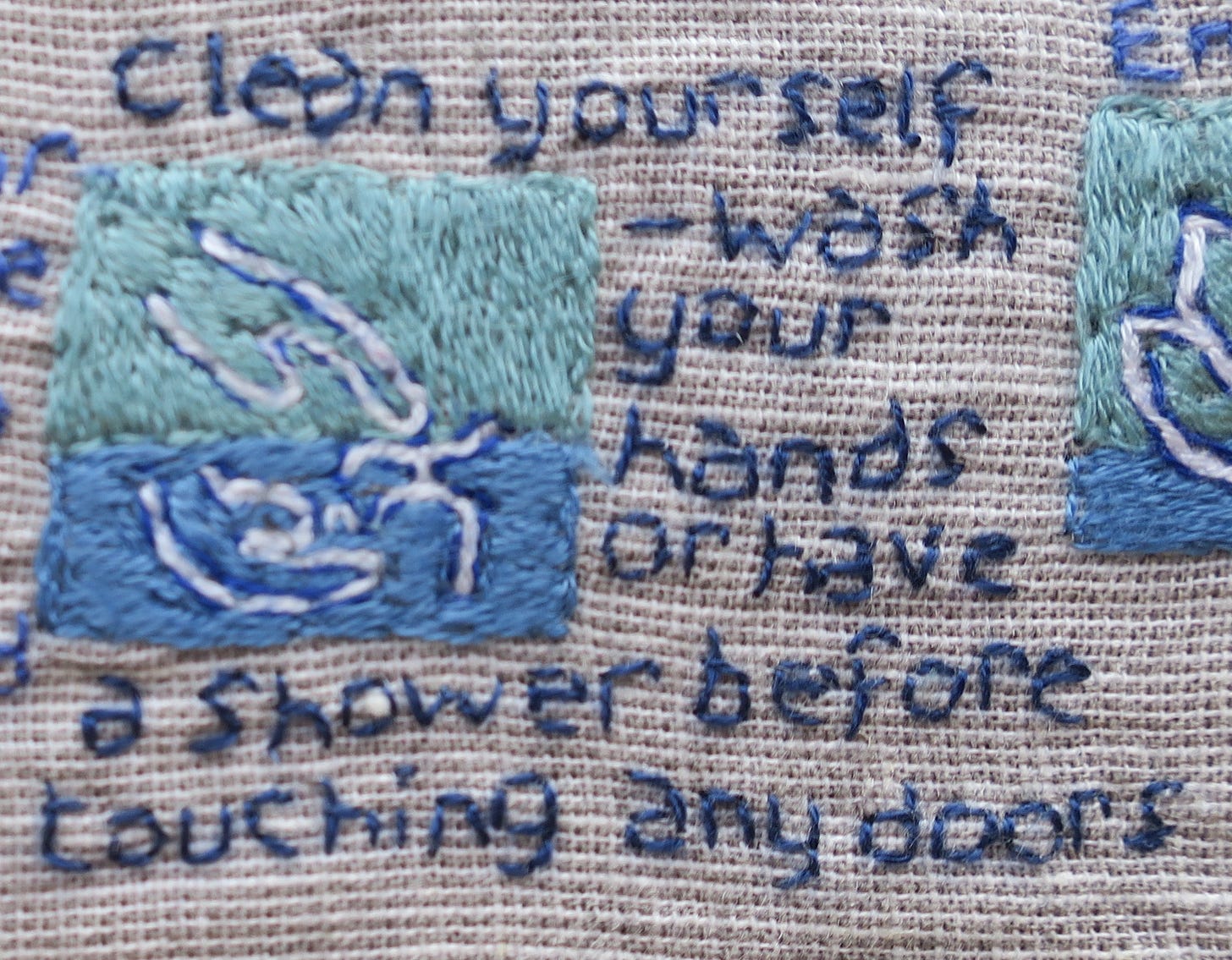

As tensions mounted, the rituals became more elaborate. We practiced donning and doffing PPE, but the limited supply meant we had to be frugal in those early days. New safety behaviours emerged: temperature checks at the door; wearing scrubs and indoor shoes; equipment and rooms cleaned with chlorine between patients; door handles wiped on an hourly schedule; windows opened come rain, hail or shine; intervening perspex screens; chairs removed from the staffroom; no shared biscuits.

We thought each new infection-control ritual would ease staff and patient anxiety over the invisible threat, but that didn’t happen. Paradoxically, with each new process, the level of fear turned up a notch. It was a delicate trade-off as we tried to contain this new organisational stress. When passing in corridors, some of us manifested a peculiar new tic. The Covid swerve was part of the new repertoire of social exchange, a symbolic communal act that only some of us found offensive; this had no bearing on infection control, and everything to do with psychological stress.

There was, though, a shared sense of responsibility behind these efforts: if we all got sick at the same time, it would compromise patient care and we had all been warned this was a significant danger. Though our collective efforts could have reduced the risk of infection somewhat, at a certain point it became apparent that many of the rituals would do nothing to contain an aerosolised virus.

However, all actions can have unintended consequences. In a twist of irony, it turned out that chlorine wrecks thermometers, so they didn’t work when needed. Each new Covid-safety procedure took time, so there was less time and staff available for patient care. But in those very early days of lockdown, we actually had time on our hands. Though we never stopped providing acute care, requests for face to face appointments almost dwindled to nothing as people stayed away.

As we transitioned from lockdown in early June, there was an expectation that normal service would resume in the NHS. For us, this meant a resumption of chronic disease monitoring, which the NHS had suspended. We faced a stark choice: either ditch the excessive non-evidence based infection control practices or consciously decide what not to do that we were justifably doing before ‘Covid’. In our practice, we recognised that maintaining the new status quo was not a zero risk strategy and would lead to measurable harms. This gave us motivation to modify our ‘new normal’ routines and try to regain at least some semblance of the old normal. It was a bumpy ride.

All employers have a legal and ethical responsibility to protect their staff. They must ensure that appropriate and adequate PPE is available, and that staff are trained in the use of it. The early PPE situation was a shambles. Supplying the care homes was an afterthought and home-carers were reduced to begging for, washing, and re-using surgical masks. Ironically, in this great scramble for PPE, there was no space to consider the actual degree to which Personal Protective Equipment protected the person.

We were told to avoid any aerosol-generating procedures (AGPs) which might spread the virus, but what defined an AGP? Was it now unsafe to use nebulisers, high flow oxygen, palliative suction and airway procedures? Advice was conflicting and we were not sure. In Italy and New York, efforts to protect staff from aerosol viral transmission led to a spike in ventilator use but as it turned out, inappropriate early ventilation hastened death in Covid-19. Non-invasive ventilation techniques were considered AGPs and thus avoided, though we would later learn these were, in fact, safe and effective.

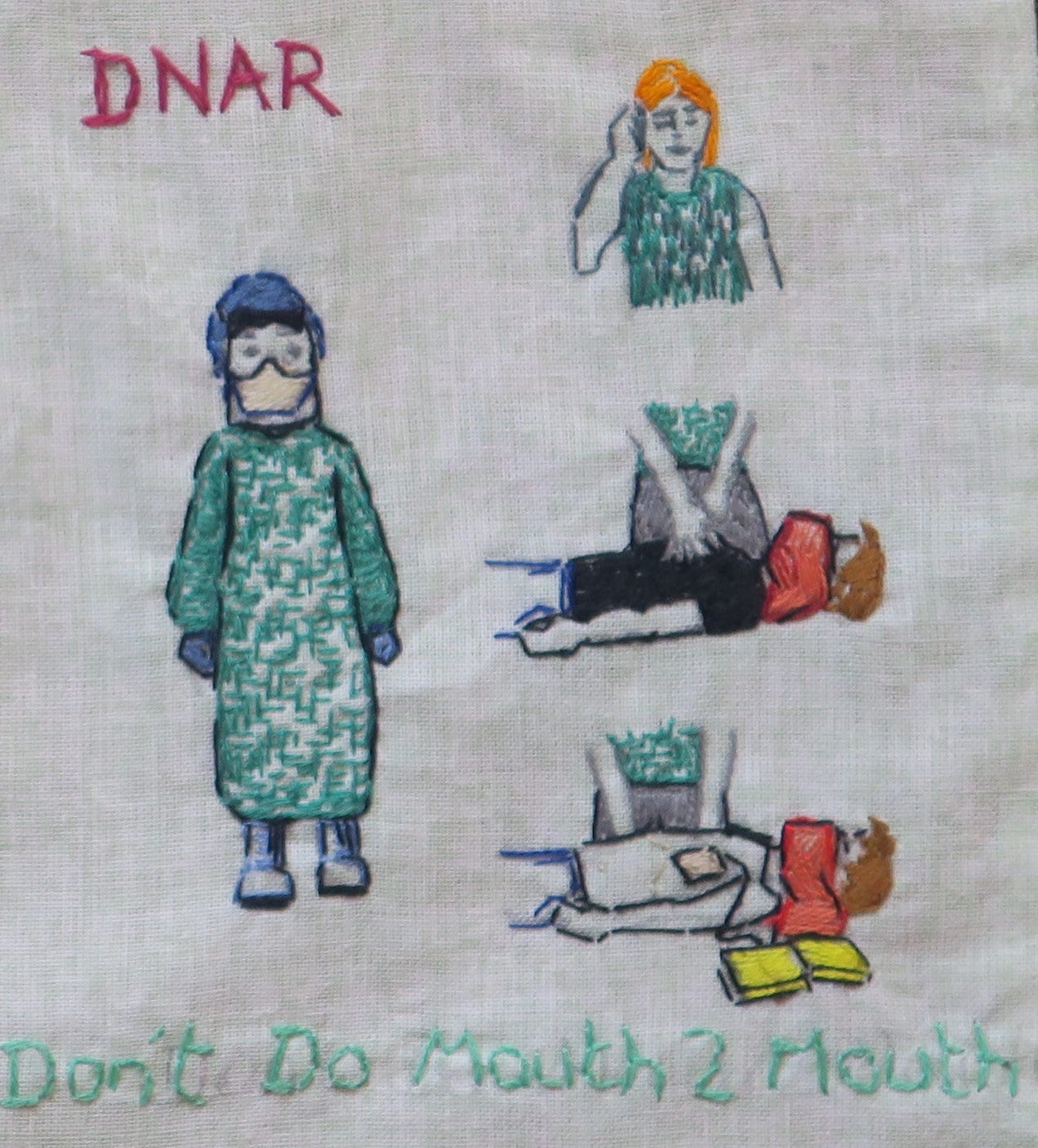

Healthcare workers had apparently been infected with Covid at resuscitation attempts. New UK resuscitation guidelines were issued – another source of disquietude for us in the community. Resuscitation in healthcare settings now required full ‘AGP PPE’, with gowns and face-fitted FFP3/N95 face masks. In one of those growing list of Covid contradictions, resuscitation outside of a healthcare setting did not stipulate face-fitted N95 masks, but recommended a towel over the face of the patient before starting compressions-only resuscitation.

We were each issued with one face-fitted mask, though that was only some time later, and was a single mask to last the whole pandemic. Face Fit testing ensures a mask seals adequately to the wearer’s face. If you can taste the bitter aerosol spray when wearing the mask, it is inadequate protection against viruses. The day of the face-fit test was the day I knew implicitly that our fluid resistant surgical masks would not stop viruses.

We heard it repeated from multiple sources that resuscitation is largely futile in severe Covid-19 illness. If the heart stops in the final stage of a Covid cytokine storm, then the body has passed the point of no return. And even if initial resuscitation was successful, there was no proven treatment for end-stage Covid-19. What was even more unsettling was to hear it said that, by extension, it would be acceptable not to attempt resuscitation on patients with acute respiratory arrest, based merely on the assumption that they had Covid-19. Yet, how often outside hospital do we know why someone has stopped breathing? For all we knew, they may have choked on a Strepsil. This was dangerous counsel which we chose to ignore.

2. Pre-emptive Planning

Normal activity in every NHS hospital was now diverted to meet the expected increased demand of coronavirus patients. Healthcare workers were “side-skilled” (a new term, which didn’t stick) or redeployed, so that they could help provide intensive care to patients. Hospitals were emptied to make space for Covid; doors were locked; screening questions were introduced for all facilities, with entry to GP practices, urgent care centres and hospitals tightly controlled; elective surgeries were cancelled; routine clinical appointments postponed; diagnostic investigations restricted; urgent care centres transformed into Covid assessment or swabbing centres; GPs were asked not to refer patients to secondary care. Anyone who could work from home was asked to do so. Most GPs adopted a ‘telephone first’ system of triage or embraced technological innovation such as total digital triage, tele-dermatology and video consultations. There were fewer face to face appointments and home visits.

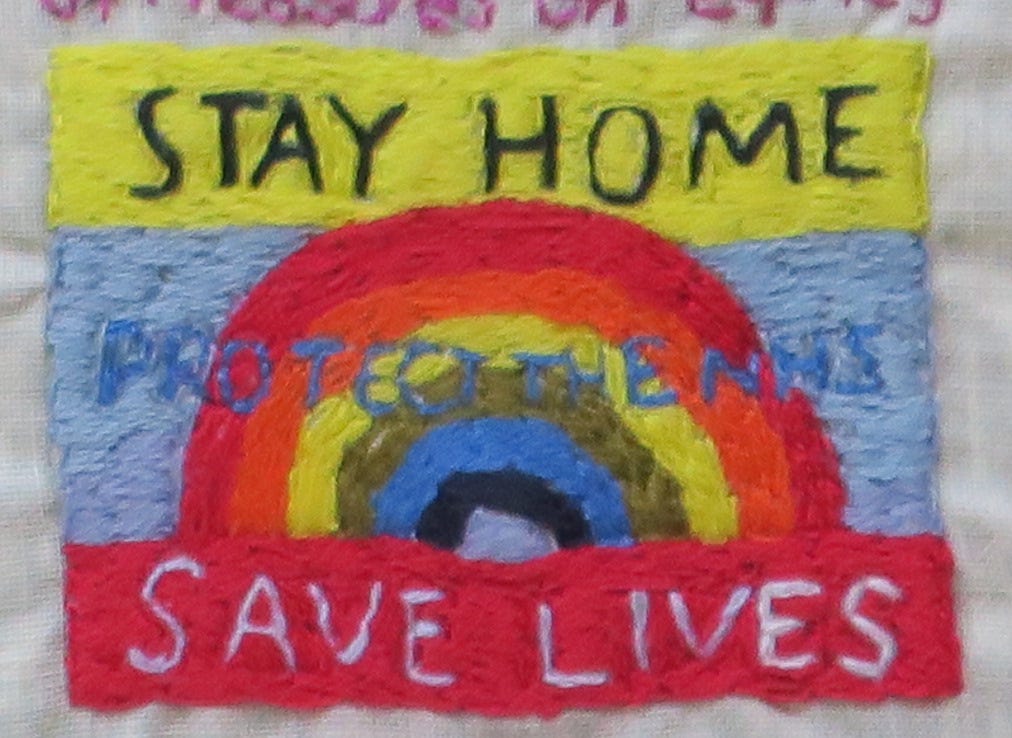

The public were told, ‘Stay at home. Protect the NHS. Save Lives.’ Healthcare was rationed in advance to ‘free up capacity’, pre-empt a staffing crisis and to ‘keep people safe’. Anticipating a tsunami of Covid death, people planned for make-shift morgues.

We went to see Dr Semmelweis at the theatre the other night. If you get a chance to watch it online I thoroughly recommend it. The hand washing and infection control to prevent deaths of mothers was clearly necessary. But his obsession with it ended up driving him loopy and losing all perspective and empathy for other people who weren’t as obsessive as him.