3. Triage (rationing)

The Lombardy physicians had painted a catastrophic picture of sickness and death, with similar stories emerging from New York city. They spoke of the need to stop hospitals becoming overwhelmed by keeping vulnerable people away, now that Covid-19 was spreading like wildfire. Protecting the people from the hospitals and protecting the hospitals from the people.

In China, despite their scrupulous use of PPE, we were told that 40 percent of early infections were hospital-acquired and two-thirds of those were healthcare workers, a ‘significant number’ of whom then died. Hospitals did not sound safe places to be in a pandemic.

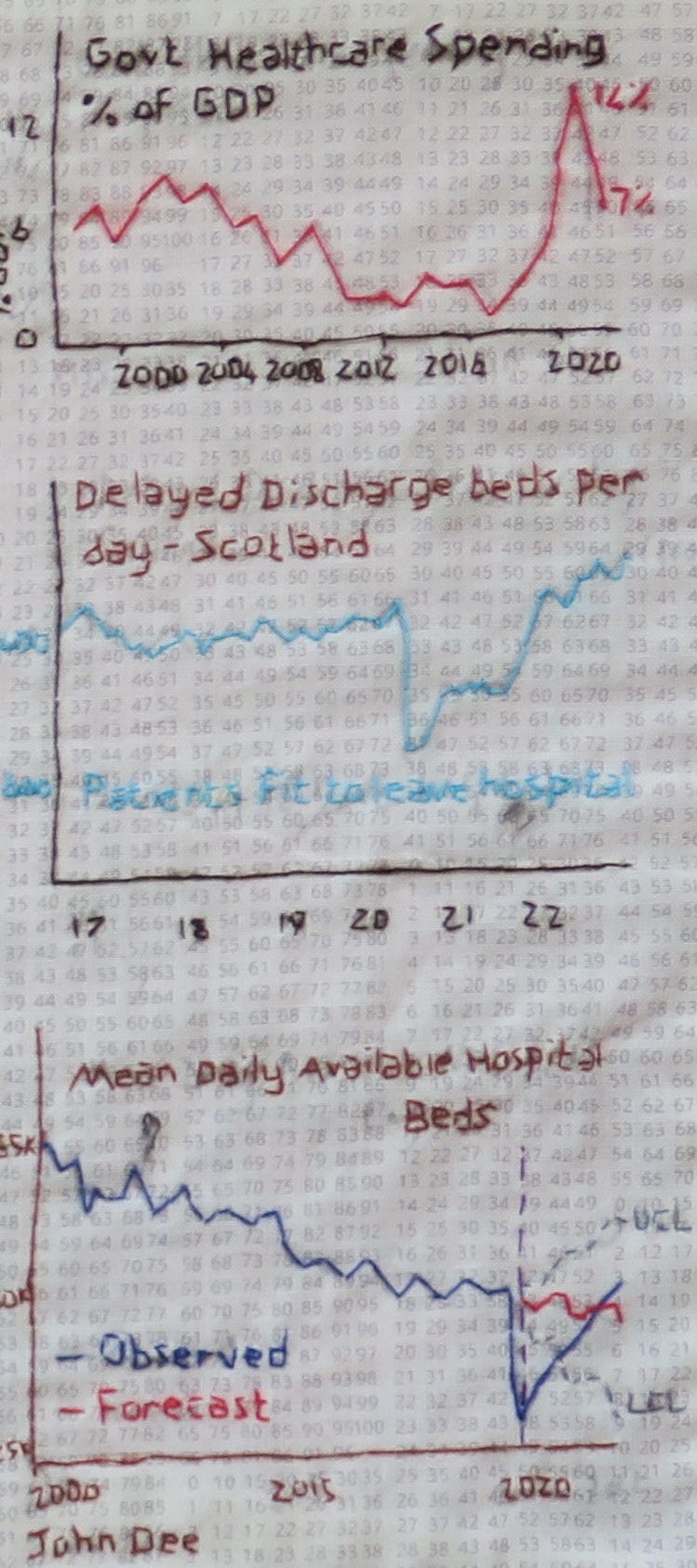

Compared with other European countries, the UK Critical care situation looked dire. On 3rd March 2020, an NHS Intensive Care doctor writing for the Guardian outlined the stark reality facing the NHS. At that time, the Covid-19 projections were 1 in 7 hospitalisation rate with as many as 20% Covid-19 patients in hospital predicted to need ICU care and a 2% mortality rate overall. He wrote, ‘I’m an ICU doctor. The NHS isn’t ready for the coronavirus crisis’. Moreover, he warned ‘intermediate treatments for pneumonia and lung failure are “aerosol-generating” (ie they risk spreading the disease) so cannot be used’.

Dyson were developing a new type of medical ventilator for the NHS, to make up for equipment shortages. The ventilator panic proved short-lived and weeks later Dyson ditched their prototypes and went back to making vacuum cleaners.

By 23rd March, the same doctor was warning Guardian readers, ‘ICU doctors now face the toughest decisions they will ever have to make’. His article explained the process of ‘resource-based triage’: the rationing of care to those most likely to survive in the event of there being insufficient beds; ventilators or staff to care for the numbers of infected people. Emphasising that this would represent a fundamental shift of medical ethics, he spelled it out for his audience,

‘Where normally the doctors’ focus is solely on what is in the best interests of an individual, when resources are overwhelmed and not all patients can be fully treated, doctors may instead have to focus on what is in the best interests of society. In normal circumstances, the General Medical Council state that doctors must avoid such decisions. If this comes to pass in the UK, doctors will be making some of the hardest decision we have ever had to make.’

All this makes for uncomfortable reading. The take-home message being the need for a clear framework for medical decision-making to cover difficult ethical choices; for transparency and public scrutiny around this process, with guidance and counsel from our medical, philosophical and political leaders.

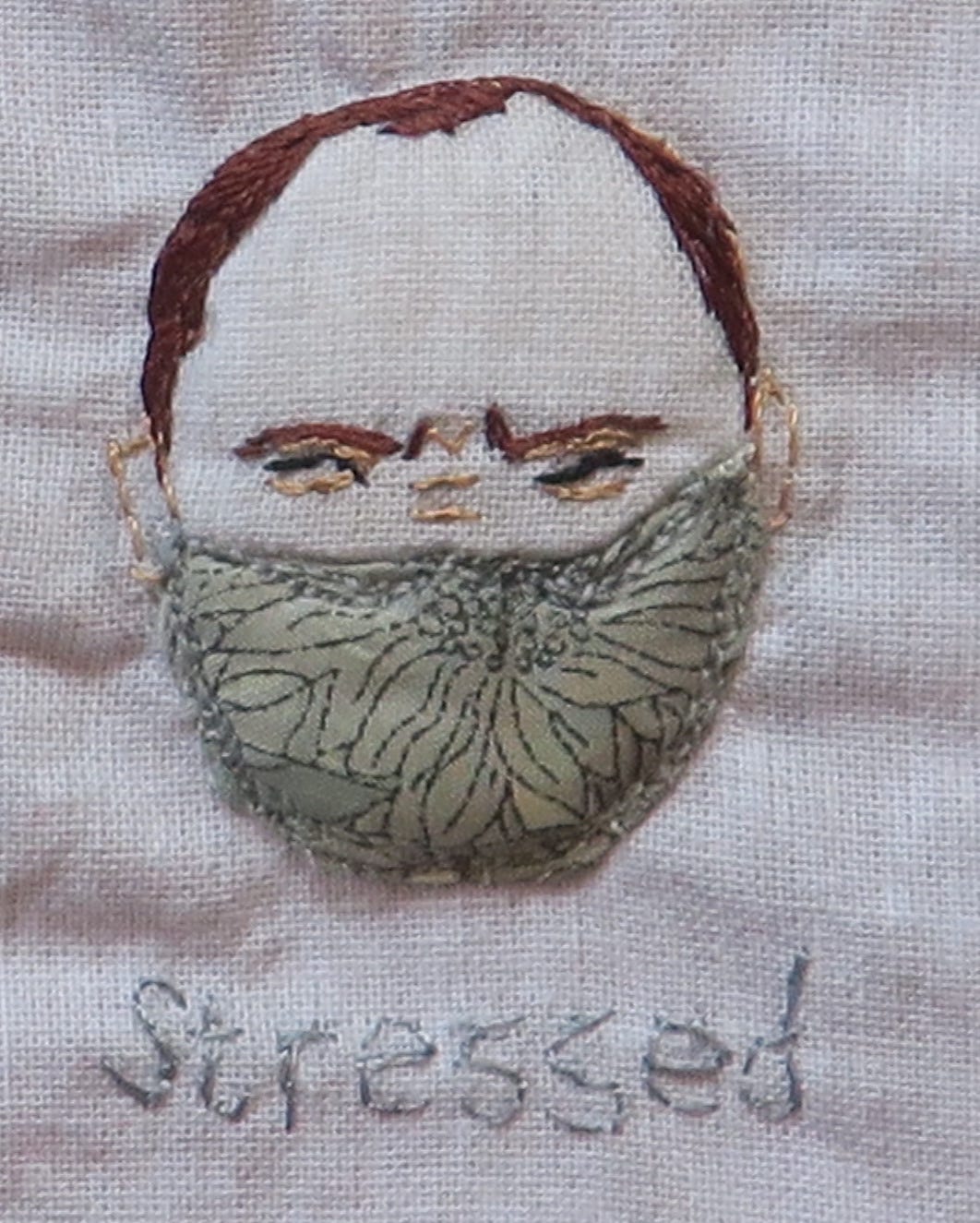

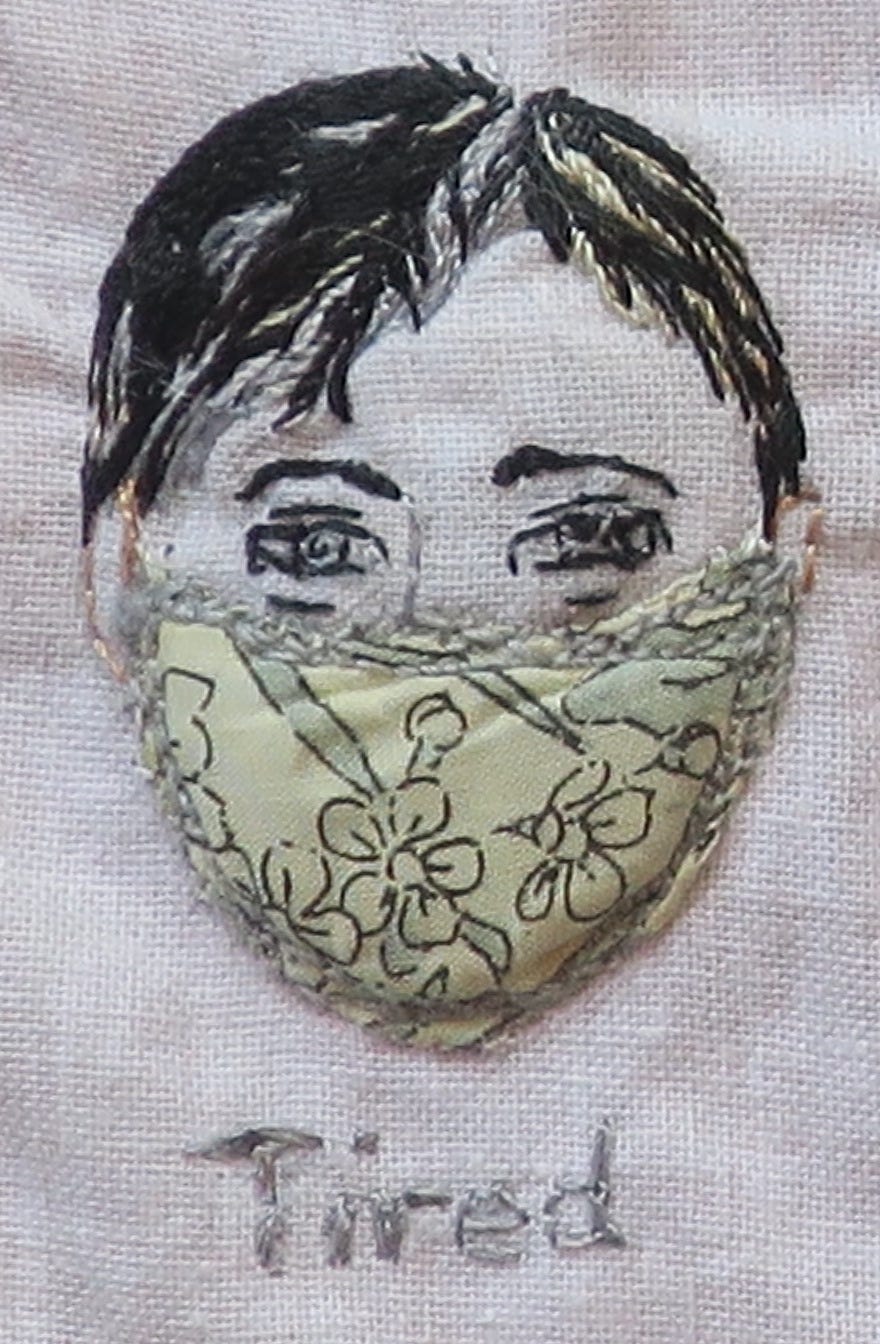

It seems our medical and political leaders were paying attention. In the first week of April 2020, a number of ethical framework documents were distributed. One government communication acknowledged the need to support healthcare staff by setting up national and regional ethical advice and support groups. It was reassuring to be told that ‘clinical decisions should continue to be guided by the principles of GMC Good Medical Practice and available evidence’. Less so, the prediction that ’Healthcare staff will need psychological support when making difficult, complex or challenging decisions outside of their normal practice’ and ‘Doctors should be assured that decisions taken in good faith, in accordance with national actions and guidance to counter COVID-19, will not be held against them’.

One wondered what it was that we would expectedly do, but which would not be held against us.

A second document, published by the BMA: ‘COVID-19 – ethical issues. A guidance note’, was considerably more disturbing, setting the tone for how decisions would need to be framed. They preface,

‘In dangerous pandemics the ethical balance of all doctors and health care workers must shift towards the utilitarian objective of equitable concern for all – while maintaining respect for all as ‘ends in themselves’.

We were left in no doubt that this was indeed a dangerous pandemic. Though acknowledging a level of statistical uncertainty, the COVID-19 mortality rate was presented, without context, as 'somewhere between 0.5 and 3.4%' with an estimate by the UK Chief Medical Officer (CMO) of ‘1% or less’ and from Wuhan, China, ‘5% of those infected were admitted to ICU, and 2.5% required mechanical ventilation’. By comparison,’ seasonal flu’ has a mortality rate in the region of 0.1%.’ A number of credible sources had already flagged the potential inaccuracy of these figures, which were open to misinterpretation, but by then this information had been widely circulated in the NHS and it was too late to amend the document.

The authors of this guidance had clearly imagined many worst case scenarios and went on to provide a suggested framework for approaching ethical dilemmas of limited resource. They warned that, at some point, we may need to stop treatment for people with significant co-morbidities, in favour of patients with more favourable outcomes.

They recommended reviewing and documenting the appropriateness of cardiopulmonary resuscitation for all inpatients who may acutely deteriorate (regardless of Covid-19 infection status) and go on to recommend,

‘If patients have sufficient background illness, co-morbidity and/or frailty that they would not be admitted to intensive care (because of the necessary restrictions on admissions), it is important that cardio-pulmonary resuscitation is not commenced in the event of a collapse. Performing advanced resuscitation for a patient for whom post-resuscitation intensive care cannot be provided would potentially cause harm to the patient, consume limited resources at a time of considerable strain, and potentially put the resuscitation team at unnecessary personal risk.’

This, on the face of it, reads as a significant departure from normal practice.

They speculated that a point may come where

‘decisions about which groups will have first call on scarce resources may also need to take account of the need to maintain essential services, in a situation where the workforce providing those services is severely depleted. This may mean giving some priority to those who are responsible for delivering those services and who have a good chance of recovery, in order to get them back into the workforce.’

It would be for Government to define the categories of essential workers, but some suggestions were given. Then to underline the potential consequences of such action, they warned,

’Giving priority to those working in essential services in this way would move beyond our usual system of resource allocation and decision-makers could face criticism for discriminating between individuals on the basis of social, rather than solely medical, factors.’

The BMA document is astonishing in scope and detail. On the one hand, distribution of resources based on medical utility is not new, albeit the given scenarios are extreme. On the other hand, discussion of triage by occupation is really quite extraordinary and shifts the Overton window of discourse. What is bewildering is that some, if not all, of these recommendations must have been considered in advance, as part of national pre-pandemic planning. Why then present these novel concepts, with their plausible ramifications, to clinicians at the eleventh hour with no forewarning? There was little time to digest and grapple with the implications of what we might be asked to carry out. The rapidity of change itself created a sense of alarm and loss of control.

In a May 2020 article, ‘The good, the bad and the ugly: pandemic priority decisions and triage’, a group of international critical care doctors’ argue that in a situation where resources are overwhelmed, it is government and society, not physicians, who must provide guidance to support triage that is no longer based on medical priorities alone.

All this betrays the mindset of the medical profession in late March/early April 2020, a time when institutional Covid-19 protocols were being drawn up. There can be little doubt that those in the driving seat would have thoroughly considered this sort of information. Projections of worst case-scenarios would prime decision-making at the highest level. It mattered less that we were ‘not there yet’, than that the possibility existed that we could soon be forced to make such choices. Many would be prepared to go to great lengths to prevent their possibilities from burdening our reality.

You're so right!

Thank you, for your contributions. We need to understand how this went so wrong. So many were killed by this bug and cure....we need to understand and create new safeguards, WE need to understand that if we have comorbidities the hospital or health "care" may indeed be the death warrent. For gosh sakes, don't trust them.

Now, accountability!

I worked hospital & LTC during the craziness. I was managing Nutrition Services, so did intakes and assessments. I saw a lot of things I can't unsee.

It was interesting to me that the nurses got into mode. Everyone just accepted what came down. Lockstep. I was the lone wolf (I was told then) who didn't buy into the madness. So much death. We didn't have a lot of covide though.