A Covid Case

Precision matters with epidemiological statistics. More so where these are used to justify or defend extreme mitigation strategies such as lockdowns. Oxford’s Centre for Evidence Based Medicine (CEBM) had an established track record for their expertise in the synthesis of evidence pertaining to flu-like viruses and pandemics. In 2020, CEBM’s Carl Heneghan, Tom Jefferson and colleagues became concerned about a series of potential errors which could lead to misinterpretation of official UK Covid-19 statistics. However, some of their findings proved unpopular and so for publicly raising concerns, they were subjected to ad hominem attacks, in which their motives were questioned and their work eventually censored. Given their experience in the field of evidence-based medicine, this new type of reaction to their work represented a curious paradigm shift.

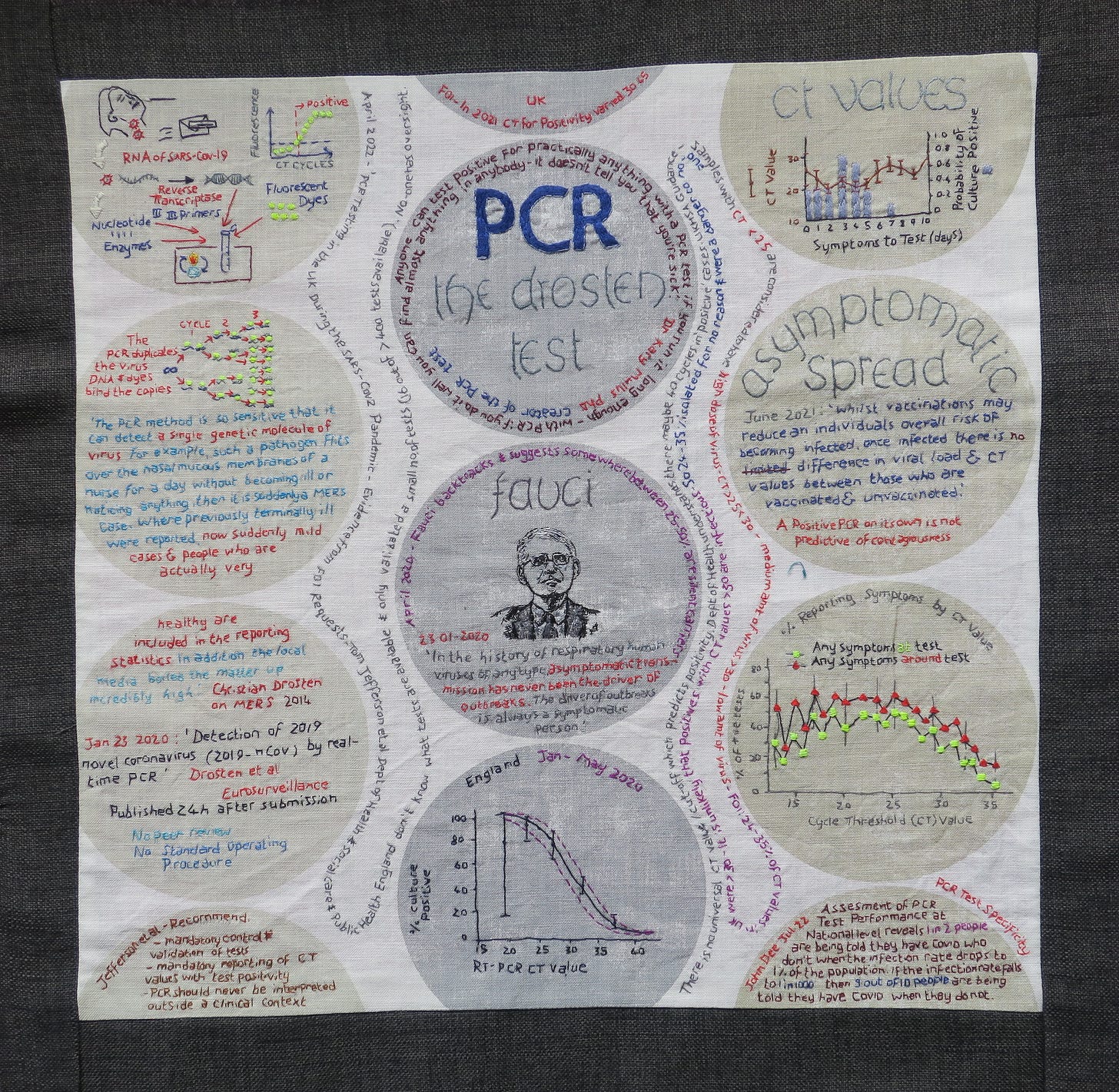

The fundamental question of what constitutes a ‘Covid Case’ was addressed in CEBM’s 2020 review article, ‘When is Covid, Covid?’. A deceptively simple question, but worth remembering that this was the basic metric used to scare people into compliance with pandemic interventions.

In the first few weeks of the pandemic, definitions changed rapidly. Before the first UK person-to-person infection transmission was recorded, diagnosis had required a relevant travel history. A possible Case was any person with a fever, new continuous cough and/or loss or altered taste or smell. A history of ‘close contact’ with a confirmed Covid-19 case in the 14 days prior to symptoms or x-ray signs consistent with Covid-19 made it a probable Case. We did no physical assessments of minimally or moderately symptomatic people so they were not included in the official tally of Cases.

A confirmed Case in the UK at the peak of the first wave required a positive PCR swab. To be eligible for PCR testing in Spring 2020, one had to be either a symptomatic healthcare or care home worker, or a symptomatic person sick enough to be assessed in a care home, Covid-19 assessment centre, or admitted to hospital. We did not have access to community testing until April 30th, though UK cases peaked on 9th April and deaths on 18th April. Later, routine PCR swabs were done on all care home and hospital admissions.

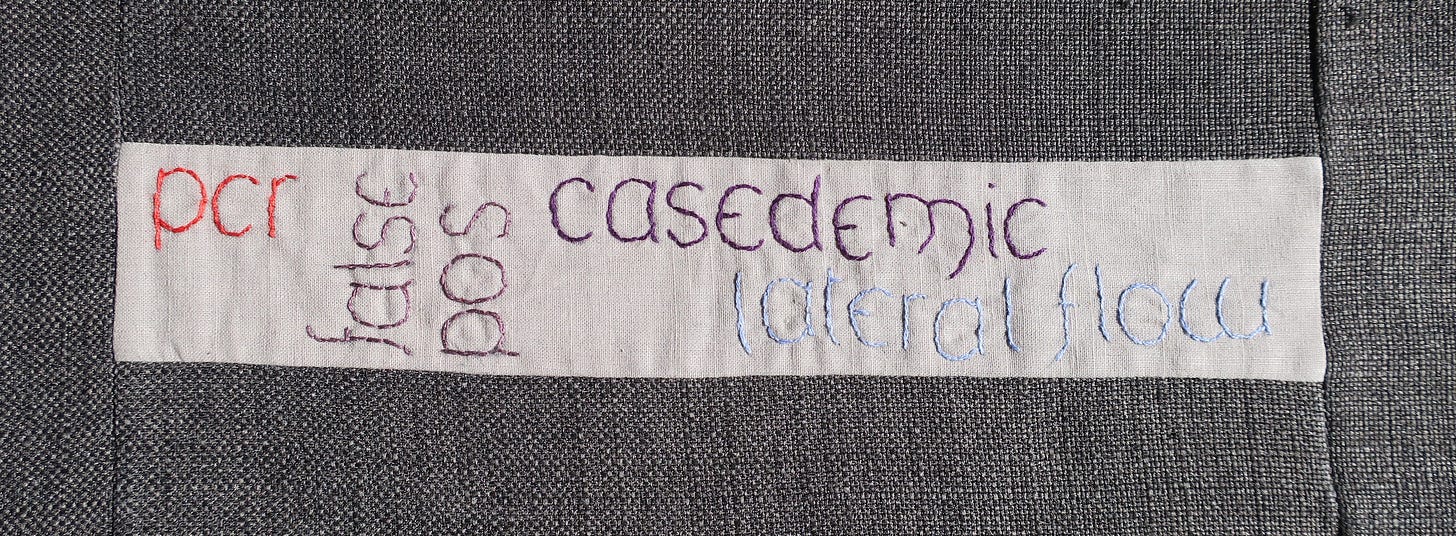

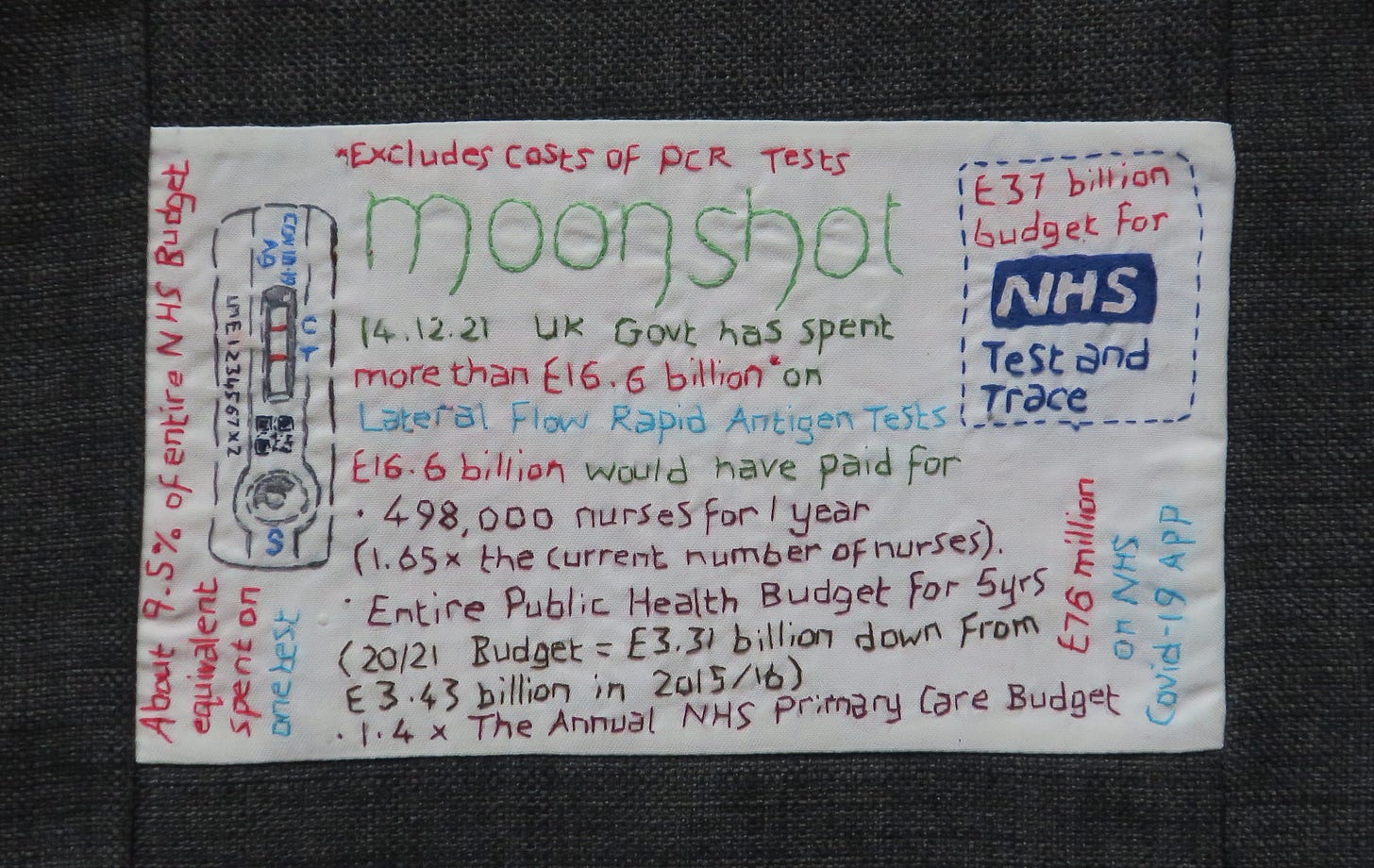

We didn’t start mass testing until May and Test & Trace until June 2020. By August 2020, a confirmed Case was now anyone with a positive test, regardless of symptoms or history of contact. These ‘Covid Cases’ were rigorously recorded, graphed and shared by a media seemingly hungry for bad news.

Once Lateral Flow Tests for Covid-19 were introduced to the public in 2021, the number of Cases initially appeared to explode, but then there was no longer any obligation to report a positive test. The media stopped their obsessive reporting of ‘cases’, but by then the numbers had lost their earlier shock value.

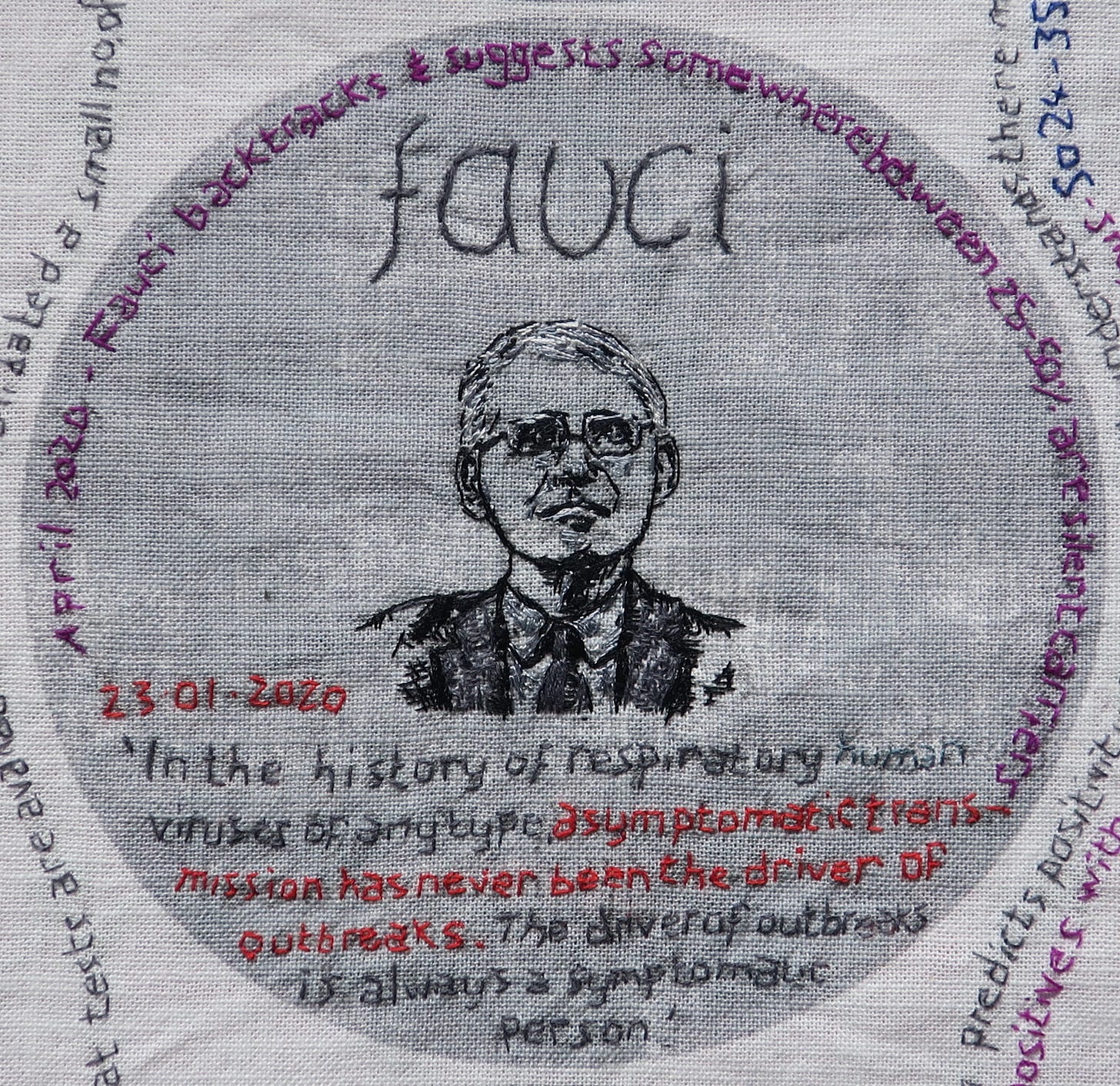

Asymptomatic Infection

In late January 2020, Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), had reassured the public that ‘asymptomatic transmission has never been the driver of outbreaks’. By June 2020 he had changed his tune, suggesting that about 25% to 45% of infected people were likely asymptomatic, and that ‘they can transmit to someone who is uninfected even when they are without symptoms.’

This changed assessment, of the potential contribution of asymptomatic spread of the virus, further fuelled anxieties about an invisible killer in our midst. Symptoms were now no longer required for a diagnosis and the official count of ‘confirmed Cases’ became an increasingly incomprehensible statistic.

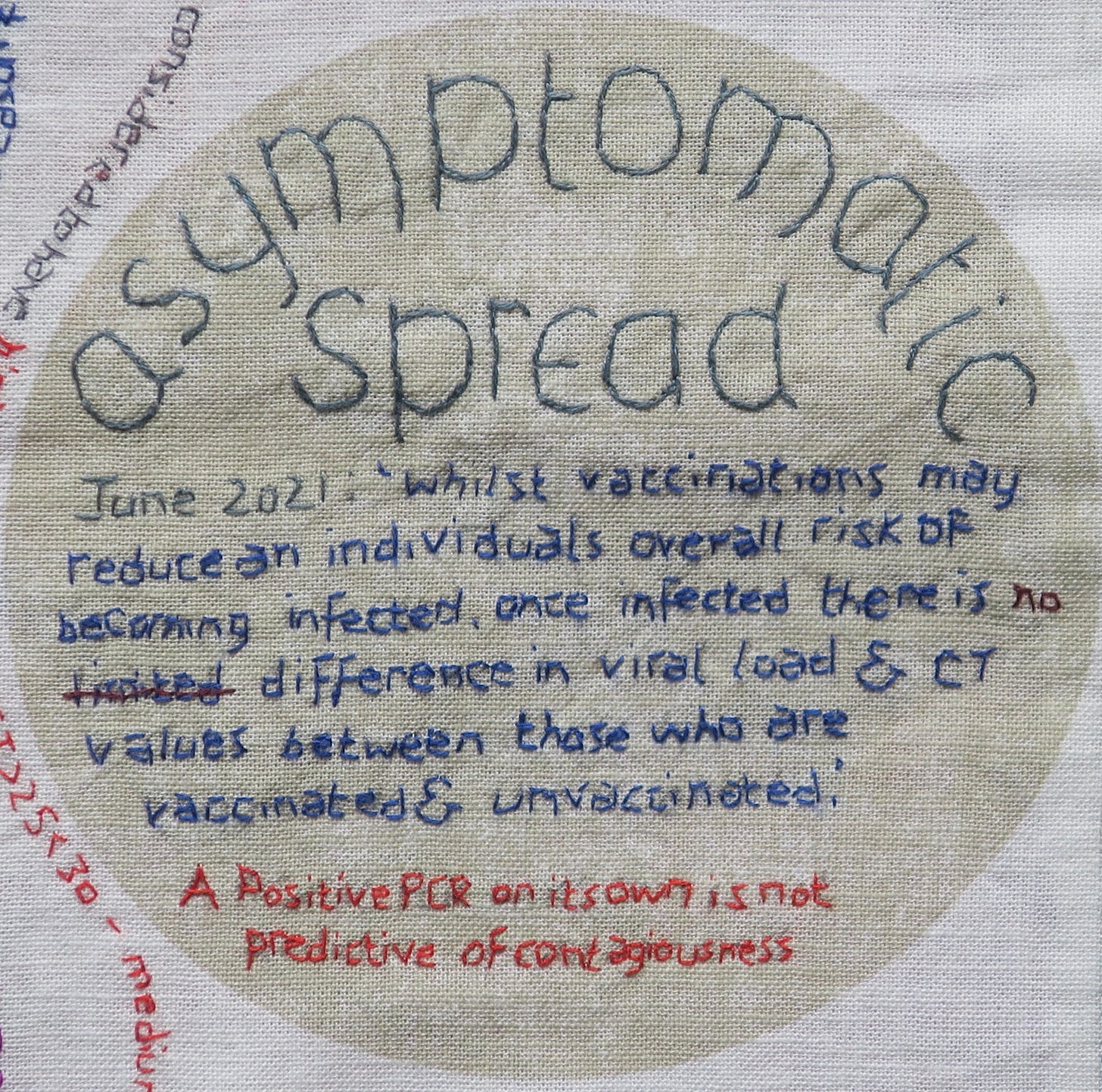

Asymptomatic infections are an epidemiologically disparate group which includes potentially infectious pre-symptomatic and pauci-symptomatic (few symptoms) people, but also non-infectious false positives and those where non-infectious mRNA fragments are detectable many weeks after infection.

A person could have another flu-like virus, but coincidentally test positive for SARS-Cov2, and this would result in a new Covid-19 diagnosis and restrictions. Early infection-control protocols recommended care workers stay off work until PCR turned negative, but some people continued to test positive for months after infection, so this advice was abandoned.

Asymptomatic transmission has been used to explain how infection can sometimes occur without a clear chain of transmission, where there is no known infectious symptomatic contact. In her book Expired, Dr Clare Craig suggests a more convincing alternative explanation for such observations is that of ubiquitous aerosol transmission. Aerosol transmission also explains why social distancing measures to control coronaviruses ultimately prove futile.

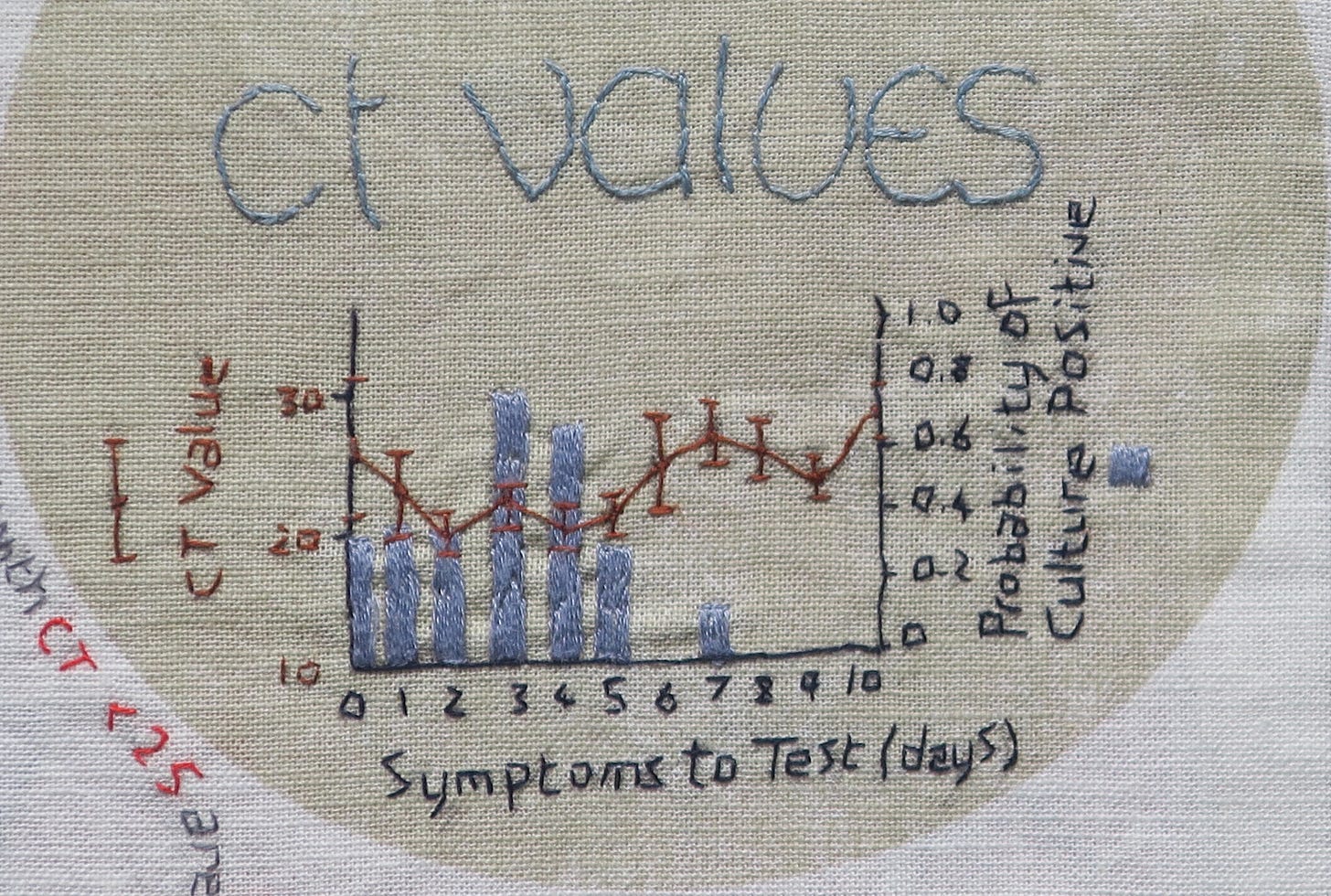

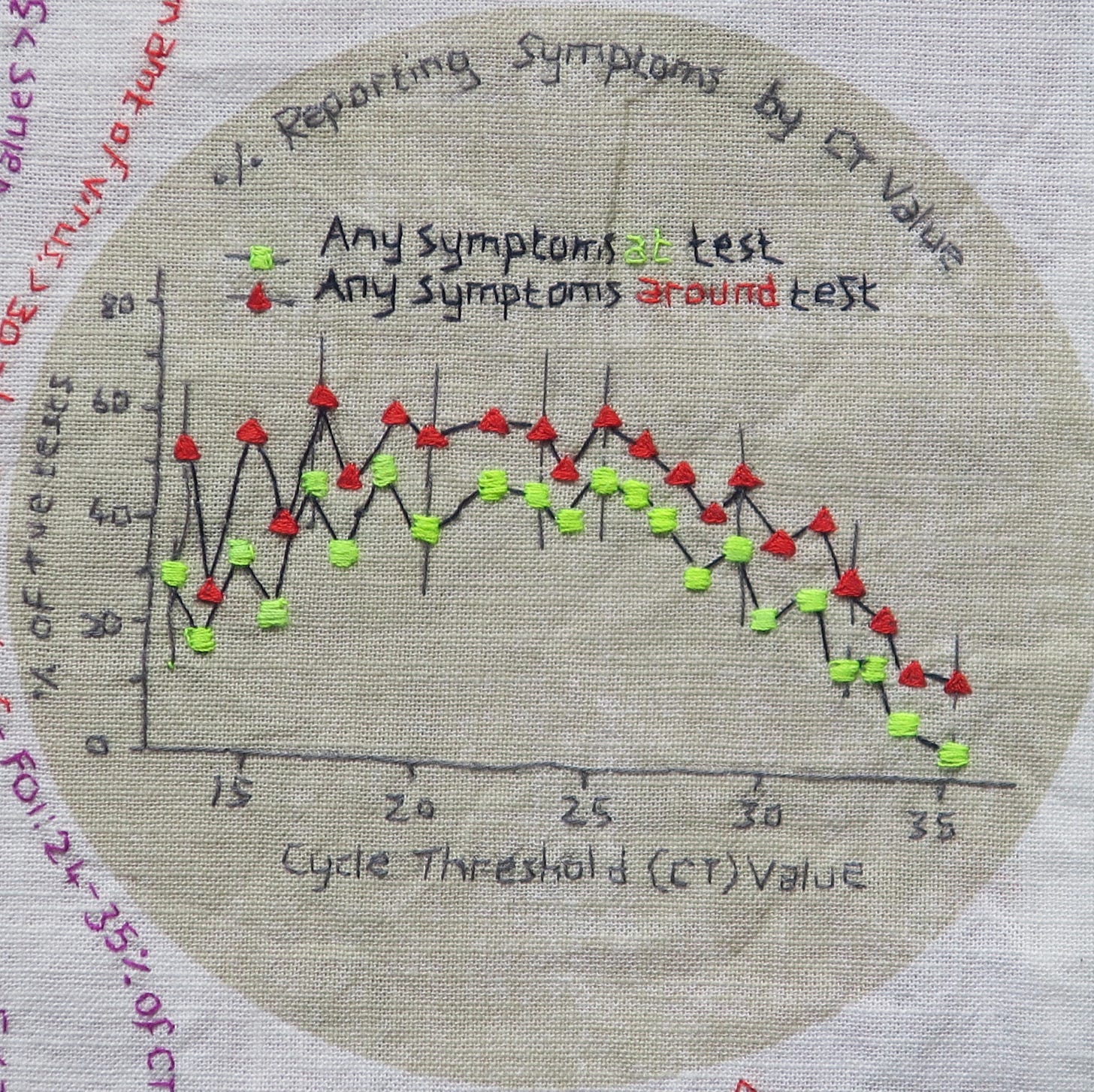

PCR tests are not a measure of infectivity and over time as the number of true infections increased, there would also be more epidemiologically irrelevant, post-infection, PCR false positives. Whilst this may seem a minor issue, the consequences could be far from benign. Incidental positives on pre-operative screening led to cancelled operations, including transplants.

With hospital swabbing protocols, a false positive swab could put a patient on a pathway to a Covid ward, leading to potential exposure to infection. It could also lead to misdiagnosis, for example bacterial sepsis or pneumonia ascribed to Covid-19 after a coincidental positive swab. Some in-patients experienced months of visiting restrictions long after hospital visiting had been reinstated. This happened whenever anyone on the ward tested positive, whether symptomatic or not and regardless of whether they had themselves recovered from the virus. In care homes, this same protocol could lead to lengthy periods of isolation.

A Covid Hospitalisation

This second metric has been used as a proxy for disease severity. In August 2020, the CEBM team noticed a flaw in UK government website data on the number of patients admitted to hospital in Wales. The numbers were implausibly high when compared to England. Raising this with gov.uk site, they were informed that “figures are not comparable as Wales include suspected Covid-19 patients while the other nations include only confirmed cases.” The figure for Wales was inflated but unfortunately, when combined with data from the other UK nations this produced misleading reports for total daily Covid-19 hospital admissions.

Heneghan’s team had earlier pointed out that it was not clear whether Covid hospital ‘admission’ meant admitted to hospital with Covid-19, admitted and diagnosed with Covid-19 while in a hospital or infected with Covid-19 while an inpatient. It was their perseverance on this question that led to the revelation that up to 25% of UK Covid ‘hospitalisations’ were probable healthcare-associated COVID-19 inpatient infections. In other words, infections acquired in hospitals were being misinterpreted as infections severe enough to require hospitalisation.